Introduction

Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) stands as a rare and distinctive myocardial disease, representing the least common among the clinically recognized cardiomyopathies. Characterized by diastolic dysfunction and restrictive ventricular physiology, RCM often maintains normal systolic function, resulting in atrial enlargement due to impaired ventricular filling during diastole. Despite its infrequency, RCM accounts for approximately 5% of diagnosed cardiomyopathies.

Pathophysiology

Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (RCM) presents as a condition characterized by increased stiffness of the myocardium, leading to accentuated filling in early diastole and a characteristic diastolic "dip-and-plateau" pattern on pressure tracings. Both inherited and acquired forms of RCM exist, affecting men and women equally. Patients exhibit reduced compliance, resulting in decreased left ventricular filling volume and subsequently reduced cardiac output. While systolic function is usually normal in the early stages, a variable reduction may develop as the disease progresses.

RCM is known to have genetic causes, with a few described mutations. The disease affects both ventricles, causing signs and symptoms of both left-sided and right-sided heart failure. Additionally, some patients may experience complete heart block due to fibrosis encasing the sinoatrial or atrioventricular nodes.

Pathologically, RCM can be classified as obliterative or non obliterative. Idiopathic RCM is non obliterative, lacking specific histopathologic changes, while obliterative RCM is rare and may result from eosinophilic syndromes, leading to thrombus-filled ventricles and fibrosis extending to the atrioventricular valves.

It is important to note that RCM can progress to a stage where symptoms of reduced cardiac output become evident, such as fatigue and lethargy. Pulmonary and systemic congestion may also occur due to increased filling pressures. The Heart Failure Society of America issued guidelines in 2010 for the genetic evaluation of cardiomyopathy, emphasizing the genetic aspect of RCM. Furthermore, obliterative RCM, associated with intracavitary thrombus, is a rare manifestation that may result from end-stage eosinophilic syndromes, presenting with additional complications such as regurgitation and different forms of endomyocardial fibrosis.

Etiology

The etiology of Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (RCM) encompasses various primary and secondary causes. Primary or idiopathic RCM includes rare conditions such as Endomyocardial Fibrosis (EMF) and Loeffler eosinophilic endomyocardial disease. Genetic and sporadic cases exist, with autosomal dominant inheritance in genetic cases, particularly involving sarcomeric protein mutations.

EMF, the most common global cause of RCM, is associated with severe prolonged eosinophilia and presents as obliterative RCM with ventricular thrombus formation. The prognosis varies, with localized lesions amenable to surgical repair, while diffuse involvement carries a poor prognosis.

Secondary RCM, characterized by infiltrative cardiomyopathies, involves the deposition of abnormal substances within the heart tissue. Amyloidosis, the most common cause of RCM in the United States, leads to multisystem protein deposition. Its cardiac involvement, primarily associated with restrictive physiology, presents challenges in diagnosis and prognosis. Other infiltrative causes include sarcoidosis, hemochromatosis, Fabry disease, and Danon disease.

Treatment-induced RCM may result from postirradiation fibrosis, affecting myocardial and endocardial tissues, or drug-induced complications, such as those associated with long-term use of antimalarial medications.

Clinical Presentation & Physical Examination

Physical Examination

- Patients with Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (RCM) often present at an advanced stage.

- Symptoms include gradually worsening shortness of breath, progressive exercise intolerance, orthopnea, fatigue, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea.

- Right-sided heart failure manifests as bilateral lower extremity edema, hepatomegaly, right upper quadrant pain, and ascites.

- Chest pain is rare but may occur in amyloidosis or secondary to angina. Palpitations are common, particularly with atrial fibrillation in idiopathic RCM.

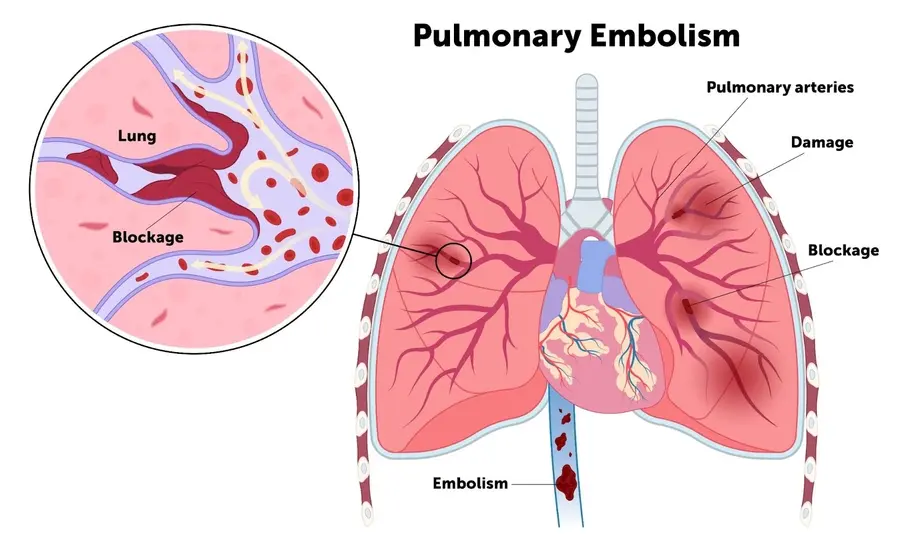

- As many as one-third of idiopathic RCM patients may present with thromboembolic complications, especially pulmonary emboli.

- Syncopal attacks may occur due to various causes, and orthostatic hypotension should be evaluated.

- Primary amyloidosis is associated with syncope and sudden death, while ventricular arrhythmias are uncommon.

- Electrical-mechanical dissociation is more usual, and conduction disturbances are common in some forms of infiltrative RCM.

- Extracardiac manifestations of systemic disorders causing secondary RCM (e.g., hemochromatosis, amyloidosis) should be assessed.

- General examination reveals patients may be more comfortable sitting due to fluid in the abdomen or lungs, with frequent ascites and pitting edema.

- Enlarged liver, weight loss, cardiac cachexia, easy bruising, periorbital purpura, and systemic findings (e.g., carpal tunnel syndrome) may suggest amyloidosis.

- Increased jugular venous pressure with rapid x and y descents indicates right ventricular filling impairment.

- Kussmaul sign, although less common, is not exclusive to RCM but may be observed.

- Cardiovascular examination shows normal heart sounds, potential S3 (uncommon in amyloidosis), and usually no S4.

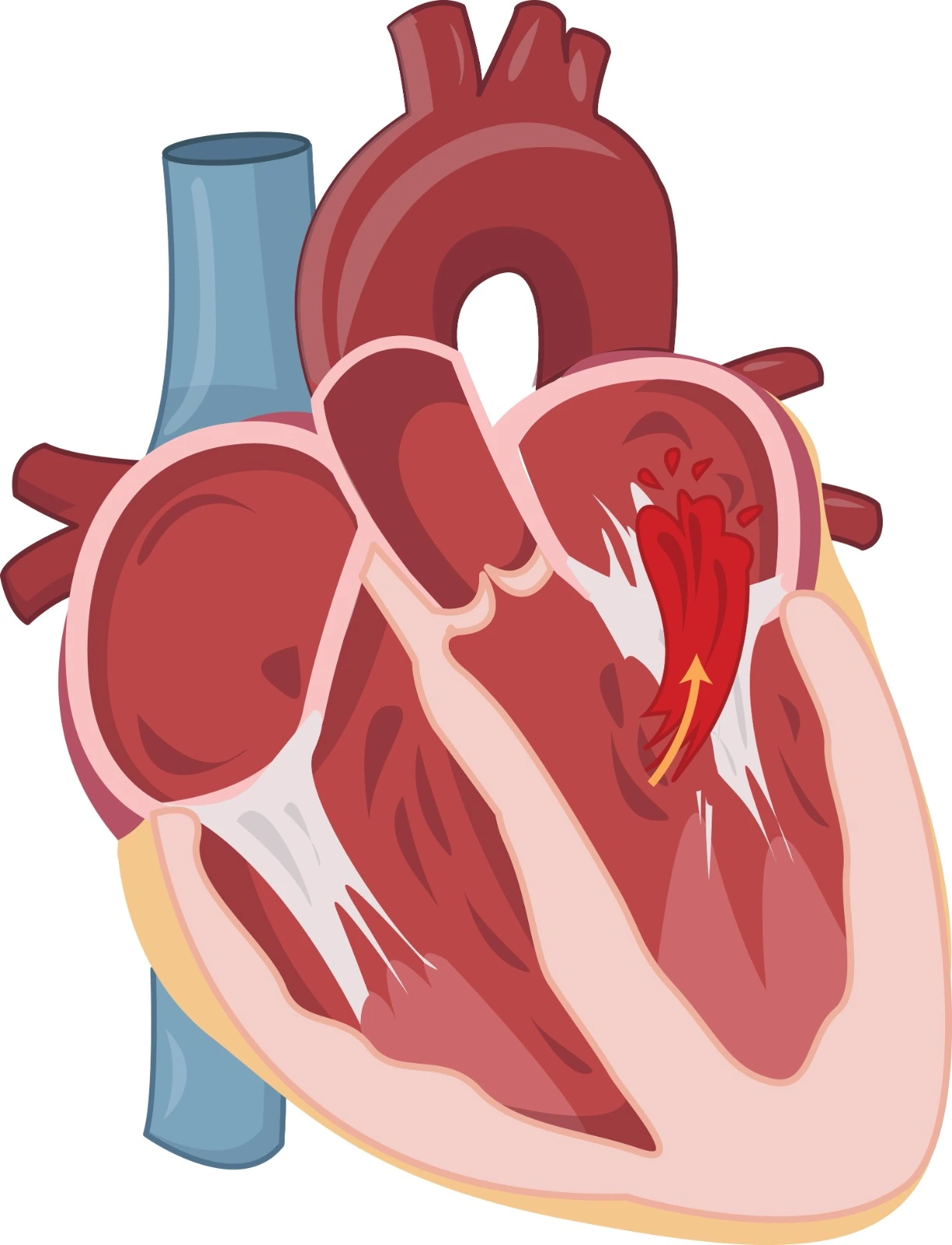

- Murmurs from mitral and tricuspid valve regurgitation are heard but are typically not hemodynamically significant.

- Respiratory examination may reveal decreased breath sounds due to pleural effusions, common in amyloidosis, with rare crepitations or rales even in advanced heart failure.

Diagnosis

Clinical Features of Constrictive Pericarditis and Restrictive Cardiomyopathy

https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/153062-differential

Table 2. Investigation of Constrictive Pericarditis and Restrictive Cardiomyopathy (Open Table in a new window)

https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/153062-workup#showall

Laboratory Studies:

- A complete blood cell (CBC) count with peripheral smear helps establish eosinophilia.

- Blood gas analysis monitors hypoxia.

- Serum electrolyte, BUN, and creatinine levels, as well as a liver function profile, should be obtained.

- Serum iron concentrations, percentage saturation of total iron-binding capacity, and serum ferritin levels are increased in hemochromatosis.

- Serum brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) levels are assessed, with higher levels indicating restrictive physiology.

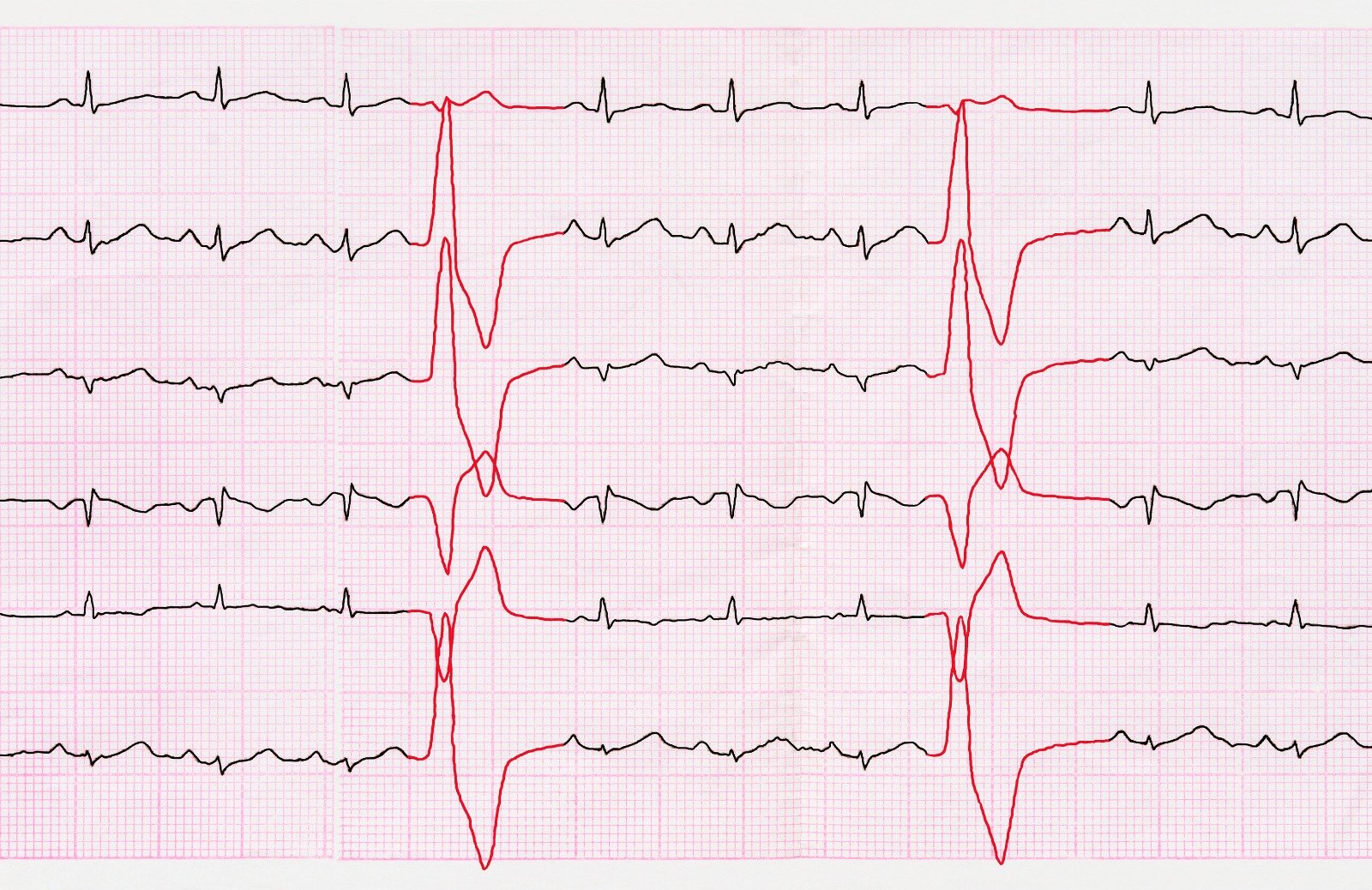

Electrocardiography (ECG):

- ECG findings vary but are abnormal in over 90% of RCM patients, with common features being atrial fibrillation and rhythm disorders.

- Torsades de pointe and ST depression mimicking ischemia may occur.

- Low-voltage QRS complexes are observed in infiltrative disease.

Radiography and Angiography:

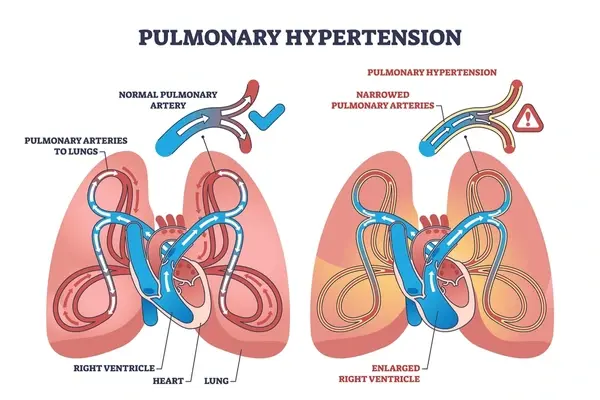

- Chest radiography typically shows manifestations of pulmonary venous hypertension and pulmonary congestion.

- Angiography may reveal a small, thick-walled cavity in eosinophilic endomyocardial disease.

Echocardiography:

- Two-dimensional imaging: Differentiates non infiltrative and infiltrative RCM based on left ventricular characteristics and atrial size.

- Doppler imaging: Reveals restriction of diastolic filling, aiding in differentiation from constrictive pericarditis.

- Pulsed-wave tissue Doppler imaging: Measures myocardial velocity gradient, aiding in differentiating restrictive and constrictive physiology.

- Strain imaging and speckle tracking: Detect myocardial deformation patterns, useful in identifying early changes.

Cardiac Catheterization:

- Ventricular pressure tracings help identify the dip-and-plateau sign, common to both RCM and pericardial constriction.

- Criteria favoring pericardial constriction include equalization of left and right ventricular filling pressures, RVSP lower than 50 mm Hg, and persistence of diastolic equalization under stress.

Other Imaging Studies:

- Radionuclide imaging: Shows increased diffuse uptake in cardiac amyloidosis.

- Cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI): Evaluates myocardial structure, perfusion, and viability, demonstrating characteristic patterns in RCM.

- Cardiac computed tomography (CCT) scanning: Limited diagnostic role but can be an alternative if CMRI is contraindicated.

Biopsy:

- Ventricular biopsy aids in establishing whether endocardial or myocardial disease is present.

- Amyloidosis diagnosis is confirmed through Congo red-stained tissue showing apple-green birefringence.

- Fine-needle aspiration of abdominal fat is a safer alternative for diagnosing amyloidosis.

- Liver biopsy is performed for hemochromatosis diagnosis.

Treatment & Management

The treatment approach for restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM) revolves around key principles informed by its unique pathophysiological characteristics.

-

Cardiac Output Management:

- The fixed stroke volume and dependency on heart rate necessitate a focus on cardiac output modulation.

- Recognizing that reverse remodeling is not a therapeutic goal, interventions should aim at relieving congestion rather than altering ventricular volumes.

-

Caution with Beta-Blockers:

- Beta-blockers may pose challenges due to their negative chronotropic and inotropic effects.

- In cases of overtly restrictive physiology, beta-blockers may worsen haemodynamic function, emphasizing the importance of careful monitoring and alternative strategies.

-

Congestion Relief as First Goal:

- Diuretics play a crucial role in relieving pulmonary and peripheral edema. However, cautious diuresis is advised to prevent hypovolemia-related reductions in stroke volume and cardiac output.

-

Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System (RAAS) Inhibitors:

- Drugs acting on the RAAS system may not demonstrate prognostic benefits and could be poorly tolerated due to hypotension.

-

Atrial Fibrillation Management:

- Atrial fibrillation, common in RCM, requires rhythm control over rate control.

- Anticoagulation is essential for patients with RCM and atrial fibrillation due to a high thromboembolic risk.

- Ventricular assist device implantation poses challenges due to the small LV cavity, and heart transplantation may be considered in selected cases.

- Recent advancements in disease-modifying therapies targeting specific proteins or nucleic acids provide promising options for certain forms of RCM.

-

Considerations for Heart Transplantation:

- Heart transplantation remains a viable option, particularly with earlier recognition and management of conditions like cardiac amyloidosis.

- Peri-operative management focuses on maintaining adequate filling pressures, sinus rhythm, managing electrolyte disturbances, and controlling systemic vascular resistance.

References:

- Rapezzi, C., Aimo, A., Barison, A., Emdin, M., Porcari, A., Linhart, A., Keren, A., Merlo, M., & Sinagra, G. (2022, October 21). Restrictive cardiomyopathy: definition and diagnosis. European Heart Journal. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehac543

- Reardon, L. (n.d.). Restrictive Cardiomyopathy: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/153062

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)