Introduction

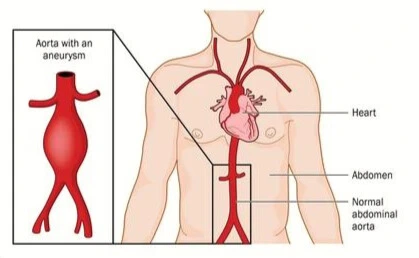

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) poses a significant threat to health and requires careful consideration due to its potential life-threatening nature. The condition is characterized by the abnormal dilation of the abdominal aorta, and its detection may be incidental or occur at the time of rupture. While true aneurysms are more prevalent, false aneurysms of the abdominal aorta, typically resulting from trauma or infection, are less common.

Anatomy

The abdominal aorta exhibits three distinct tissue layers—intima, media, and adventitia—each contributing to its structural and functional properties. The gradual reduction in diameter from the thoracic to the infrarenal portions is accompanied by changes in elastin and collagen content. Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) commonly originate below the renal arteries and vary in size, shape, and extent.

The anatomical considerations for surgical and endovascular interventions involve assessing renal and visceral artery involvement, iliac artery conditions, and the length of the infrarenal aortic neck. The choice between retroperitoneal or transabdominal surgical approaches and the location of the aortic cross-clamp depend on these factors. Additionally, preserving hypogastric artery outflow is crucial to prevent complications such as impotence and colon ischemia.

Inflammatory aneurysms, a subset of AAAs, are characterized by a thick inflammatory peel and are associated with retroperitoneal fibrosis. The presence of adhesions with the duodenum and fibrosis further complicates these cases. Understanding the diverse characteristics of AAAs and considering the associated anatomical factors are essential for effective planning and execution of surgical interventions, aiming to prevent complications and ensure optimal patient outcomes.

Pathophysiology

Abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAAs) arise from a failure of major structural proteins, elastin and collagen, within the aorta. The inciting factors are not fully understood, but a genetic predisposition is evident. Most AAAs occur in individuals with advanced atherosclerosis, although the association is likely not causative. The development of AAAs involves a complex interplay of proteolytic degradation, inflammation, biomechanical wall stress, and molecular genetics.

The normal diameter of the infrarenal aorta is smaller than 3 cm, with a diameter of 1.5 cm in women and 1.7 cm in men after the age of 50. When the diameter exceeds 3 cm, it is considered an AAA, even if asymptomatic. AAAs typically manifest with thinning of the media, marked loss of elastin, and chronic adventitial and medial inflammatory infiltrate.

Research has identified mechanisms crucial in AAA development, including proteolytic degradation of aortic-wall connective tissue, inflammation, biomechanical wall stress, and molecular genetics. Metalloproteinases, specifically matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), play a role in tissue remodeling, with increased expression and activity observed in individuals with AAAs. The balance between MMPs and their inhibitors influences the degradation of elastin and collagen, contributing to aneurysmal deterioration.

Immunoreactive proteins and infectious agents, such as Chlamydia pneumoniae and Treponema pallidum, have been associated with AAA development, though a direct cause-and-effect relation remains unproven. Insights from molecular genetics, particularly gene microarray analysis, have revealed the upregulation of genes involved in extracellular matrix degradation, inflammation, and other processes associated with AAA formation.

Atherosclerosis, while commonly observed in individuals with AAAs, is considered a nonspecific secondary response to vessel-wall injury induced by multiple factors. The intricate interplay of these factors underscores the dynamic and complex nature of AAA formation, necessitating further research for a comprehensive understanding and effective therapeutic approaches.

Etiology

Abdominal aortic aneurysms are influenced by a diverse array of risk factors, each contributing to different aspects of their development, expansion, and rupture. Key points include:

- Tobacco abuse emerges as the primary modifiable risk factor for AAA development.

- Smoking cessation, while beneficial, does not fully reverse the damage incurred.

- Advanced age and male gender are associated with increased prevalence, especially in the 65 to 80-year age group.

- Women, non-Caucasians, and certain ethnic groups exhibit lower prevalence rates.

- Family history and genetic factors contribute significantly, increasing the risk by two- to fivefold.

- Syndromic monogenetic disorders may be associated with specific types of aortic aneurysms.

- Association with Other Aneurysms:

- Presence of other large vessel aneurysms, such as femoral or popliteal, elevates the risk for AAA.

- Combined thoracic and abdominal aortic aneurysms are not uncommon, with varying prevalence between genders.

- Atherosclerotic Risk Factors:

- Systemic atherosclerosis often coexists with AAA, though the pathophysiology is distinct.

- Coronary artery disease and peripheral arterial disease are prevalent in individuals with AAA.

- Other Influencing Factors:

- The association of obesity with AAA is inconclusive, with a mild positive correlation.

- Moderate alcohol consumption may have a protective effect, while higher levels could increase the risk.

- Fruit and vegetable consumption is mildly associated with reduced AAA development.

- Diabetes mellitus is negatively associated with AAA, indicating a distinct process from atherosclerosis.

- Medications used for diabetes may have a potential protective effect against AAA development.

Clinical Presentation

Clinical presentations of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) can be categorized into three main groups:

- The majority of patients with intact AAA are asymptomatic.

- Discovery may occur through screening, routine physical examination, or imaging studies for unrelated conditions.

- Physical examination alone is often insufficient to exclude asymptomatic AAA.

-

-

Symptomatic but not ruptured:

- Symptoms may indicate rapid expansion, compression of surrounding structures, or an inflammatory or infectious process.

- Common symptoms include abdominal, back, or flank pain, with or without AAA rupture.

- Other manifestations may include limb ischemia, fever, and malaise.

- Rupture must be considered in patients with abdominal pain.

-

-

Symptomatic and ruptured:

- The clinical presentation of ruptured AAA varies.

- Only a minority of patients are aware of their AAA before rupture.

- Classic presentation includes severe pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile abdominal mass in about 50% of cases.

- Ruptured AAA can be challenging to recognize; 20 to 30 percent of patients in the emergency department have a known AAA history.

- Misdiagnosis as renal colic, perforated viscus, diverticulitis, gastrointestinal hemorrhage, or ischemic bowel occurs in approximately 30% of cases, even after seeking medical attention.

Diagnosis

A confirmed diagnosis of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is achieved through imaging studies that reveal the presence of the aneurysm in individuals suspected of having AAA due to identified risk factors or during a physical examination.

Physical Examination

The physical examination plays a crucial role in the assessment of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), with the following key points:

- Most clinically significant AAAs can be palpated during routine physical examination.

- Palpation sensitivity varies based on the examiner's experience, aneurysm size, and patient size.

- In one study, 38% of AAA cases were identified through physical examination, while 62% were incidentally detected on radiologic studies.

- Palpation of the aorta in the upper abdomen is essential, with AAA typically palpated just above the umbilicus.

- The size of the aneurysm is estimated during the examination.

- Proper palpation of the abdomen does not pose a risk of precipitating aortic rupture.

- Ruptured AAA and Physical Findings:

- Ruptured AAA can present with subtle physical findings despite dramatic pain onset.

- Normal vital signs may be observed due to retroperitoneal containment of hematoma.

- Pulsatile Abdominal Mass:

- Virtually diagnostic of AAA, but found in fewer than 50% of cases.

- More likely to be present with a ruptured aneurysm.

- In an obese abdomen, palpating an AAA is challenging.

- Even in known cases, vascular surgeons may be unable to palpate a pulsatile mass in 25% of instances.

- Classic presentation (pain, hypotension, tachycardia, pulsatile mass) occurs in less than 30-50% of cases.

- Common misdiagnosis includes renal colic; renal artery dissection may mimic symptoms.

- Blood Pressure Measurement:

- Systolic blood pressure reversal (higher in the arm than in the thigh) may indicate AAA.

- Bilateral upper-extremity blood pressure differences >30 mm Hg suggest subclavian artery stenosis.

- Bruits or lateral propagation of the aortic pulse wave may offer subtle clues.

- Popliteal artery aneurysms can coexist with AAAs (25-50% of cases).

- Flank ecchymosis (Grey Turner sign) indicates retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

Imaging

The imaging approach to abdominal aortic aneurysms involves tailored methods based on clinical presentation:

- Confirmatory vascular imaging for suspected cases.

- Abdominal ultrasonography for asymptomatic AAA, with consideration of its limitations.

- CT as the imaging choice for symptomatic AAA, offering valuable insights into rupture and instability.

- Limited use of CT and MR imaging for asymptomatic cases, mainly for surgical planning and postoperative monitoring of aortic graft repairs.

Treatment & Management

The evolving landscape of unruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) treatment emphasizes a nuanced approach based on size, symptoms, and patient risk factors. Key points to consider include:

- Indications for Treatment:

- Treatment is recommended when the AAA diameter reaches 5 to 5.5 cm, rapidly enlarges by >0.5 cm over six months, or becomes symptomatic.

- Open surgical repair, historically the gold standard, is now complemented by endovascular repair, especially in older and higher-risk patients.

- Emergency Repair for Ruptured AAA:

- Ruptured AAA necessitates emergency repair, with endovascular approaches demonstrating superior results if anatomically suitable, despite high mortality rates.

- Long-Term Outcomes and Follow-up:

- For unruptured AAAs, endovascular repair shows comparable long-term outcomes to open repair.

- Close monitoring of AAA patients who do not undergo repair is crucial, with periodic ultrasounds every 6 to 12 months.

- Endovascular Approaches for Complex Aneurysms:

- Fenestrated and branched endovascular repair (F/B-EVAR) offers advantages, especially in high-volume vascular centers.

- Factors influencing the choice of stent graft and its durability impact the efficacy of F/B-EVAR procedures.

References:

- Shaw, P. M. (2023, March 21). Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm. StatPearls - NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470237/

- Facs, S. A. R. M. (n.d.). Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: Practice Essentials, Background, Anatomy. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1979501

- Overview of abdominal aortic aneurysm. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-abdominal-aortic-aneurysm

- Epidemiology, risk factors, pathogenesis, and natural history of abdominal aortic aneurysm. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/epidemiology-risk-factors-pathogenesis-and-natural-history-of-abdominal-aortic-aneurysm

- Screening for abdominal aortic aneurysm. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 26, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/screening-for-abdominal-aortic-aneurysm

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)