Introduction

Constrictive pericarditis is a condition characterized by the thickening and fibrosis of the pericardium, leading to impaired diastolic filling of the heart. The chronic nature of this condition often results in pericardial inflammation, fibrotic scarring, calcification, and restricted cardiac filling.

Pathophysiology

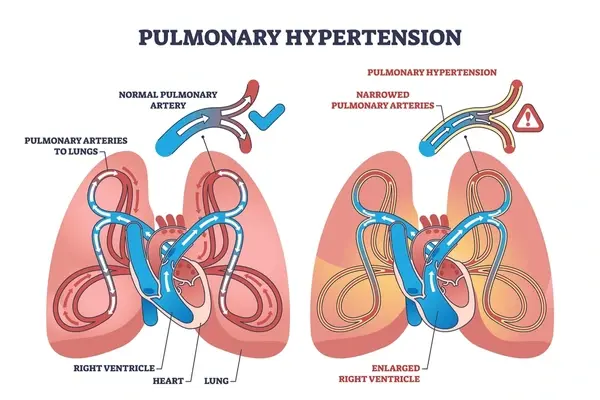

The pathophysiology of constrictive pericarditis involves a restrictive, thickened pericardium that limits cardiac volume expansion. Unlike the normal pericardium, the inelastic pericardium in constrictive pericarditis hinders the transmission of intrathoracic pressure changes to the heart chambers during inspiration, leading to impaired ventricular filling. Ventricular interdependence occurs as the right heart volume expands due to the interaction with the left ventricle. The early diastolic filling is rapid, and as the disease progresses, ventricular volumes and stroke volumes decrease.

Hemodynamically, the disease manifests as a dip-and-plateau waveform on pressure tracings, distinguishing it from restrictive cardiomyopathy. The preservation of myocardial function in early diastole helps differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy, as systolic function is typically affected only in the late stages. Over time, symptoms of congestive heart failure develop due to inadequate stroke volume, leading to venous engorgement and decreased cardiac output. The clinical presentation and hemodynamic findings underscore the importance of distinguishing constrictive pericarditis from other cardiac conditions for appropriate management.

Etiology

The etiology of constrictive pericarditis can be broadly classified into common, less common, and rare forms. Common causes encompass idiopathic cases, infections (bacterial, viral, and fungal), radiation therapy, cardiac surgery, and connective tissue disorders. Less common causes involve neoplasms, uremia, drugs, trauma, and myocardial infarction. Rare forms include occurrences after implantation of cardiac devices, Mulibrey nanism, sclerotherapy for esophageal varices, and chylopericardium. The varied etiological spectrum underscores the importance of a comprehensive evaluation in diagnosing and managing constrictive pericarditis.

To summarize, constrictive pericarditis exhibits a diverse range of etiologies, as evidenced by case series from tertiary care centers:

Idiopathic or Viral Factors:

Accounts for 42 to 61 percent of cases.

Post-Cardiac Surgery:

Represents a significant contributor, ranging from 11 to 37 percent.

Post-Radiation Therapy:

Contributes in 2 to 31 percent of cases, particularly after Hodgkin disease or breast cancer.

Connective Tissue Disorders:

Occurs in 3 to 7 percent of cases.

Postinfectious Causes:

Tuberculous or purulent pericarditis contributes to 3 to 15 percent of cases.

Miscellaneous Causes:

Malignancy, trauma, drug-induced factors, asbestosis, sarcoidosis, and uremic pericarditis collectively contribute to 1 to 10 percent of cases.

This variety in etiological factors highlights the importance of a comprehensive assessment when diagnosing and managing constrictive pericarditis.

Clinical presentation

History:

Constrictive pericarditis poses a diagnostic challenge due to its diverse symptomatology, making reliance on clinical history alone nearly impractical. Patients often experience a gradual onset of symptoms over several years, rendering them unaware until prompted. These symptoms overlap with those of right-sided congestive heart failure (CHF), adding complexity to the diagnostic process. Dyspnea, universally present and frequently the initial symptom, is accompanied by fatigue, orthopnea, and manifestations such as lower-extremity edema, abdominal swelling, and discomfort. Nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant pain, when present, are attributed to hepatic or bowel congestion.

Physical Examination:

In the early stages, physical findings may be subtle, demanding meticulous examination to avoid overlooking the diagnosis. Advanced stages may manifest with significant illness features, including muscle wasting, cachexia, or jaundice. Noteworthy cardiovascular findings include elevated jugular venous pressures, sinus tachycardia, and an often impalpable apical impulse. The presence of a pericardial knock, indicative of sudden ventricular filling cessation, is notable, occurring along the left sternal border.

While a cardiac murmur is typically absent, pulsus paradoxus, if present, rarely exceeds 10 mm Hg. The Kussmaul sign, elevation of systemic venous pressures with inspiration, is a common but nonspecific finding. Gastrointestinal and pulmonary manifestations may include hepatomegaly, ascites, spider angiomata, palmar erythema, and dependent edema. Right-sided heart cardiac catheterization aids in direct assessment, revealing a characteristic ventricular pressure waveform and contributing to a comprehensive understanding of the condition. The interplay of clinical history and physical examination findings is crucial in navigating the diagnostic intricacies of constrictive pericarditis.

Evaluation

The evaluation of patients suspected of having constrictive pericarditis involves a comprehensive approach that includes clinical history, physical examination, and various diagnostic tests. The following key points summarize the diagnostic process:

Initial Evaluation

- Patients with suspected constrictive pericarditis should undergo initial evaluation with electrocardiography, chest radiography, and echocardiography.

- Cardiac catheterization is often performed prior to surgical intervention for confirmation of diagnosis and assessment of coronary anatomy.

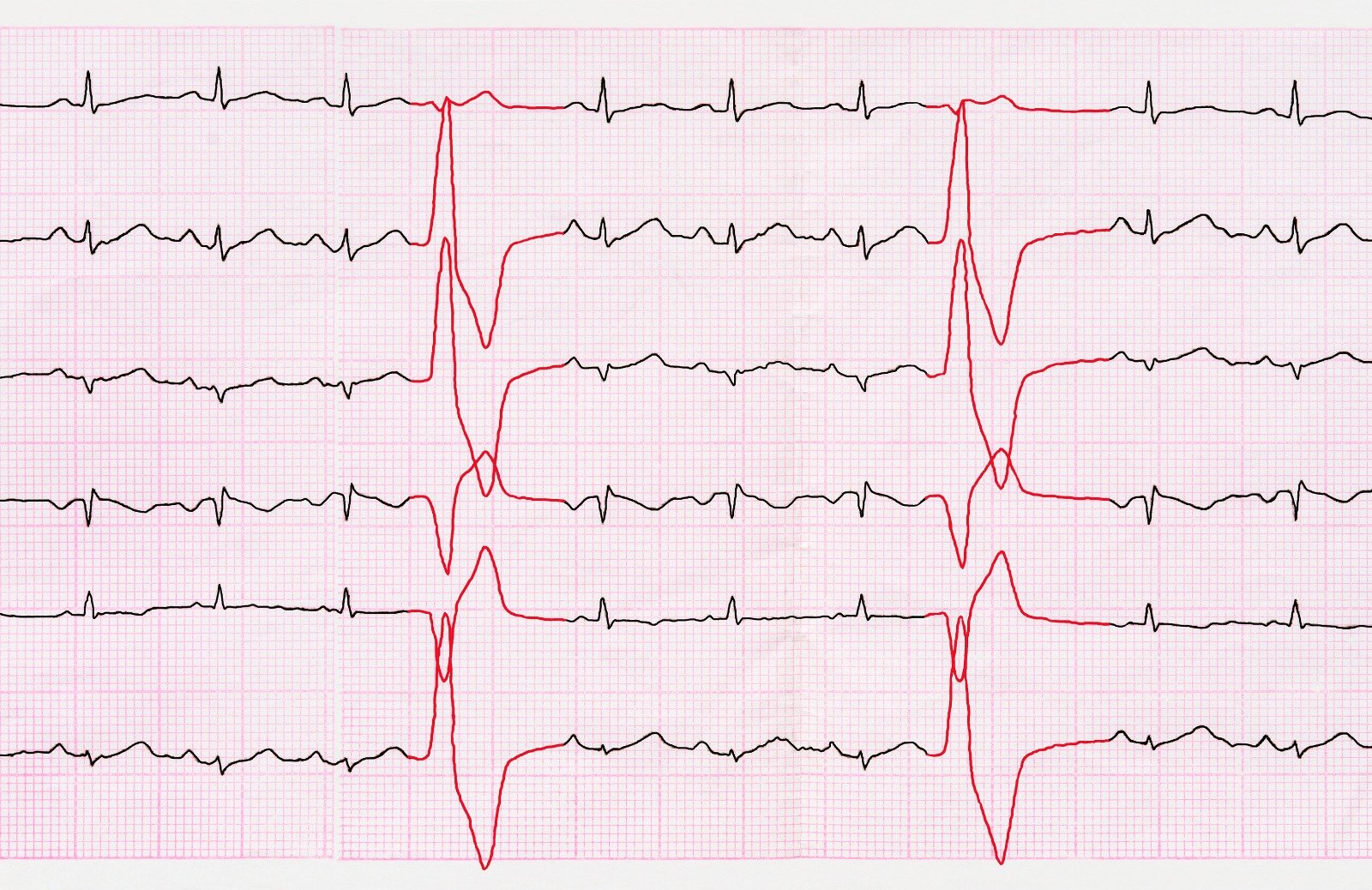

Electrocardiography

- No pathognomonic findings.

- Common findings include nonspecific ST and T wave changes, tachycardia, and, in advanced cases, atrial fibrillation.

Chest Radiograph

- Pericardial calcification, especially in conjunction with clinical symptoms, is highly consistent with constrictive pericarditis.

- Absence of calcification does not exclude the diagnosis.

Echocardiography

- Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) is essential.

- Two-dimensional and M-mode echocardiography reveal increased pericardial thickness, abnormal septal motion, and atrial enlargement.

- Doppler echocardiography is critical for diagnosing constrictive pericarditis, with specific findings related to abnormal ventricular filling and respiratory variation.

Computed Tomography (CT) Scan

- Useful for detailed anatomical information and perioperative planning.

- Findings include increased pericardial thickness, calcification, and assessment of adjacent structures.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Gated cardiac MRI provides direct visualization.

- Helpful for detailed anatomical information and assessing pericardial inflammation.

- May offer additional information for preoperative planning.

Hemodynamic Evaluation

- Invasive evaluation may be needed, especially if echocardiographic findings are inconclusive.

- Major findings include increased right atrial pressure, prominent x and y descents, Kussmaul's sign, and square root signs in RV and LV diastolic pressure tracings.

Plasma BNP

Elevated plasma BNP is less common in constrictive pericarditis compared to other cardiomyopathies.

Differential Diagnosis

- Distinguish constrictive pericarditis from cardiac tamponade, restrictive cardiomyopathy, and chronic liver disease.

- Hemodynamic findings and imaging studies play a crucial role in differentiation.

Treatment and Management Strategies

Surgical Intervention: Pericardiectomy

- Pericardiectomy stands as the definitive treatment, demonstrating rapid hemodynamic and symptomatic improvements.

- Surgical mortality ranges from 5% to 15%, with optimal outcomes when performed earlier in the disease course.

- Complete pericardiectomy, either through anterolateral thoracotomy or median sternotomy, is the potential cure.

- Extensive pericardial decortication, even with the use of excimer laser for severe adhesions, is crucial.

- Complications may include bleeding, arrhythmias, and ventricular wall ruptures.

- Postoperatively, 80-90% of patients achieve NYHA class I or II, but abnormal diastolic filling may persist.

Medical Management: Pharmacologic Therapy

- Inflammatory components necessitate a different approach from acute pericarditis.

- Rilonacept, an IL-1 cytokine trap, gained FDA approval in 2021 for pericarditis treatment and recurrence reduction.

- Steroids may be effective in subacute cases, but caution is advised due to potential complications.

- Diuretics help relieve congestion but require careful monitoring to avoid compromising cardiac output.

- Tailored medications for the underlying cause are crucial, and specific therapies address complications like atrial arrhythmias.

- Beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers are generally avoided due to the compensatory role of sinus tachycardia.

Perioperative Considerations and Outcomes

Timing is critical, with better results observed in early interventions, minimizing calcification and heart failure risk.

- Mortality risk is influenced by preoperative conditions, comorbidities, and the timing of pericardiectomy.

- Evidence suggests persistent diastolic filling abnormalities post-surgery, emphasizing the importance of early intervention.

- Ongoing research explores alternative access methods like video-assisted thoracoscopy to enhance diagnostic and therapeutic options.

- Cardiac mortality and morbidity are linked to preoperative myocardial atrophy or fibrosis, detectable by CT scanning.

Postoperative Care and Consultations

- Postoperative challenges may include low cardiac output, requiring tailored interventions like sympathomimetic infusions or mechanical support.

- Consultation with a cardiologist aids in interpreting imaging and hemodynamic data, while cardiothoracic surgeons are essential for pericardial procedures.

- Referral to specialized centers may be necessary if diagnostic or therapeutic modalities are limited.

References:

- Constrictive pericarditis: Clinical features and causes. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/constrictive-pericarditis-clinical-features-and-causes

- Constrictive pericarditis: Diagnostic evaluation. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/constrictive-pericarditis-diagnostic-evaluation

- Constrictive pericarditis: Management and prognosis. (n.d.). UpToDate. Retrieved December 20, 2023, from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/constrictive-pericarditis-management-and-prognosis

- Edwards, W. M. (n.d.). Constrictive Pericarditis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/157096

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)