Triggers and risk factors of PVC

- Alcohol and caffeine intake.

- Recreational drug use and stimulant drugs (amphetamines, cocaine, etc.)

- Electrolyte abnormalities.

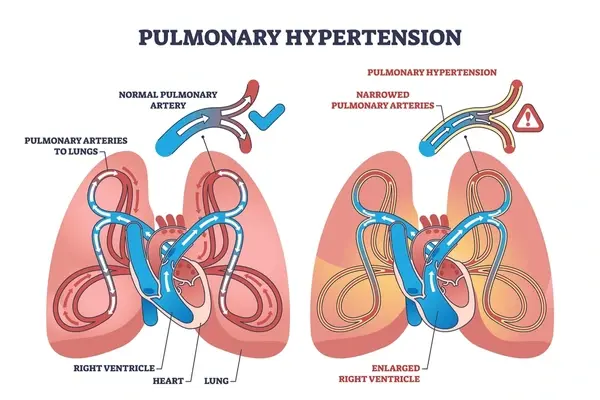

- Hypoxia.

- Uncontrolled hypertension.

- Thyroid gland abnormalities (hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism)

- Supra-therapeutic Digoxin levels.

- Acute decompensated heart failure.

- Anemia.

- Psychological risk factors.

- Perimenopausal women.

High-risk patients

High-risk patients criteria

- High PVC burden (> 10 to 15%) or

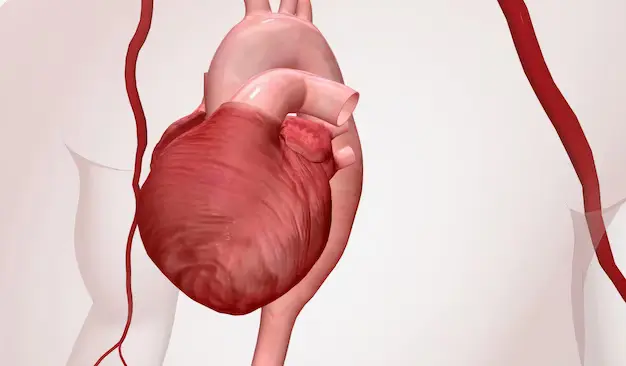

- Cardiomyopathy that is PVC-induced or

- History of syncope or

- Preexisting cardiac structural disease or

- Preexisting electrical conduction system disease or

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities even if LVEF is normal

Goals of therapy

- Reverse or reduce the risk of developing cardiomyopathy.

- Reduce the risk of sudden cardiac death.

- Reduce the risk of ventricular arrhythmias.

Management of patients with PVC-induced cardiomyopathy

Before therapy initiation, patients should be assessed, and risk factors and triggers should be mitigated.

- Beta-blockers (typically metoprolol and carvedilol) are the first-line agents to reduce the burden of PVC; unless the patient has heart failure, catheter ablation is preferred.

Beta-blockers are effective in reducing PVC symptoms and preventing recurrence, but they have no effect on the ventricular myocardium. They improve PVC that results from excessive sympathetic stimulation.

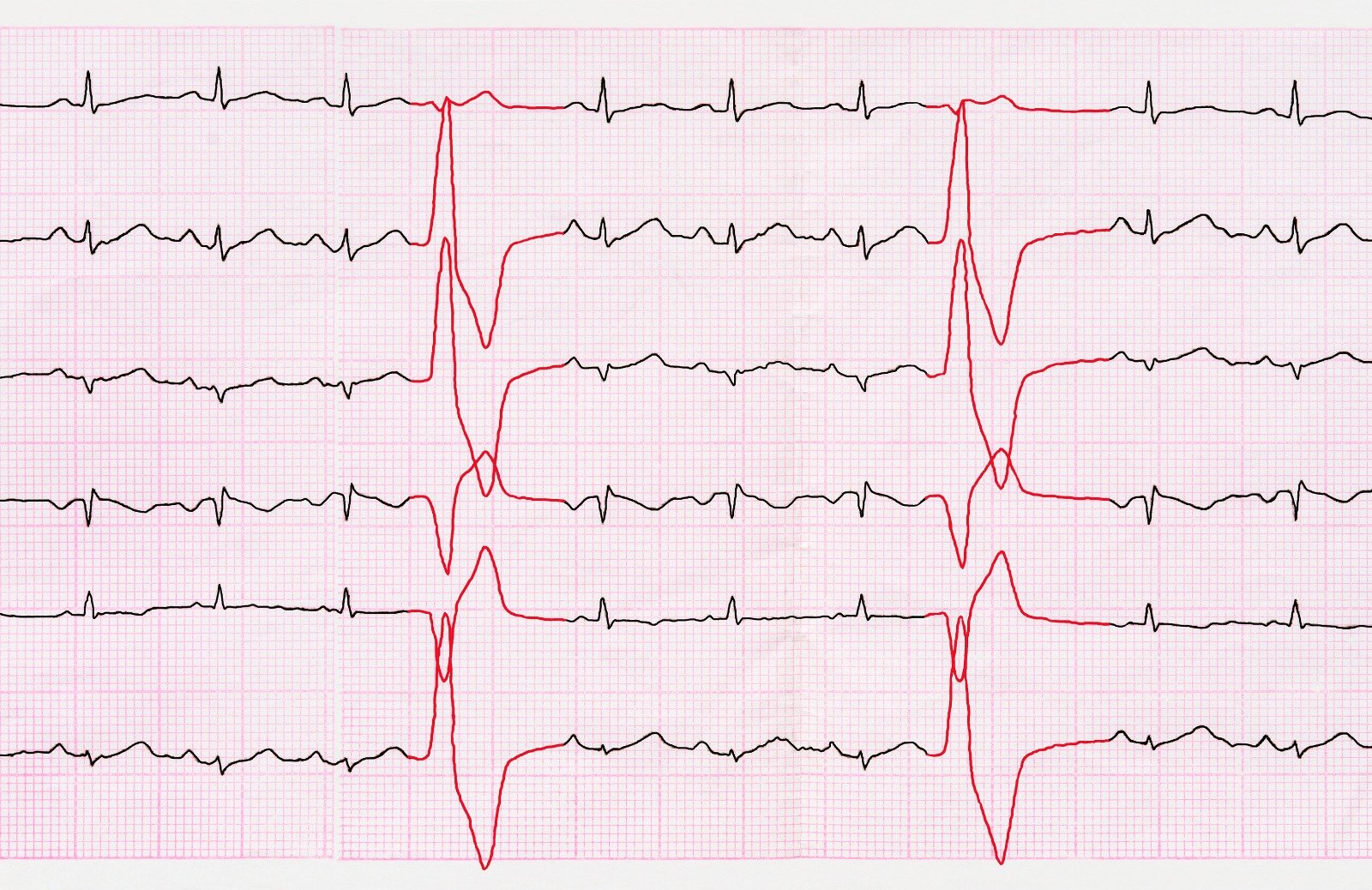

An ambulatory ECG is done after 3 months of therapy initiation to assess response. Continuation and titration of beta-blocker doses are done depending on PVC and symptoms improvement; if the symptoms and PVC are improved, then beta blockers should be continued, but if after one month there is no improvement in symptoms or PVC burden, then catheter ablation is usually considered, especially if the PVC is monomorphic or antiarrhythmic drugs are initiated alternatively.

If the patient desires to wean the beta blocker after symptom relief, this can be done by reducing the dose gradually after 6-12 months of treatment, and a 24-hour Hotler recording can be periodically repeated. Keeping the patient on a low dose might help prevent a recurrence.

Avoid calcium channel blockers in patients with cardiomyopathy.

- Catheter Ablation: If the patient does not respond properly to beta blockers, catheter ablation is the other option. It is also considered the first line in patients with heart failure; it reduces or eliminates PVC, and in patients with cardiomyopathy, it can lead to left ventricular function recovery.

Catheter ablation vs. antiarrhythmic: this depends on predictors of procedure success and the patient's preference.

In most patients, full LVEF recovery from ablation might take 3-6 months, and one-third of patients might take 3-4 years. Cardiac monitoring should be done after approximately 3 months of ablation to assess the PVC burden.

Predictors of ablation success (patients who will most likely respond properly to catheter ablation):

- monomorphic PVC.

- High PVC burden (> 10 to 15%).

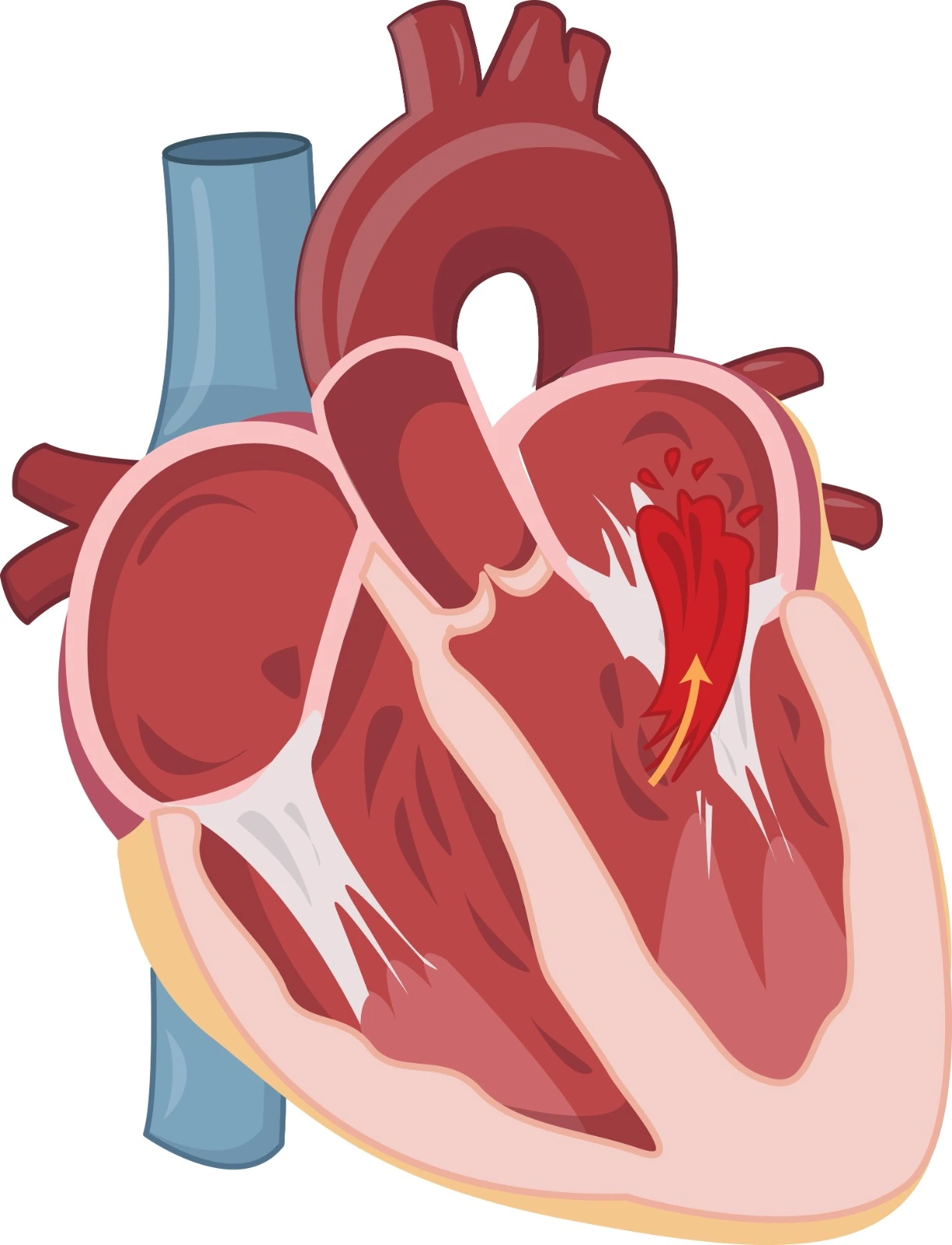

- Right ventricular outflow tract origin (RVOT)

Predictors of ablation failure:

- Multiple PVC morphologies

- Epicardial origin.

- Papillary muscle origin

- short or decreased earliest local activation time.

Complications

- Circulatory complications: stroke, myocardial infarction, mitral or aortic valve damage

- Myocardial perforation.

- Coronary artery injury.

- Lethality.

- Antiarrhythmic drugs: they can be used in patients who are not surgery candidates or who don't prefer ablation.

- Amiodarone: least proarrhythmic drug.

- Ranolazine: an oral anti-angina drug that is suggested to be beneficial in PVCs.

Low-risk patients

Low-risk patients criteria

- Patients who don't have cardiomyopathy and/or inherited arrhythmia syndrome

Management

- Asymptomatic patients with low premature ventricular complex burden

(<1 percent or 1000 PVCs/day) and no structural heart disease: observation and elimination of triggers; no pharmacological therapy or catheter ablation is necessary.

- Symptomatic patients and/or high premature ventricular complex burdens:

- Beta-blockers are the first-line option.

- Non-dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (CCBs): if the patient's LVEF is normal, there is no structural heart disease, and fascicular origin PVCs if beta blockers were not effective.

- Antiarrhythmic drugs or catheter ablation if treatment with beta blockers or CCBs was not effective or tolerated.

Start class 1C (Propafenone, Flecainide) antiarrhythmic drugs rather than ablation if there are multiple PVC morphologies, or low-frequency PVC (<3 percent or 500 PVCs/day), patients with risks that might limit a successful procedure, or patients preference to avoid ablation.

Note: Do not use class 1C antiarrhythmic drugs in patients with cardiomyopathy or left ventricular dysfunction.

PVCs in Pregnancy management

Beta-blockers, mainly metoprolol and bisoprolol, can be used. Ablation, if needed, should be postponed until postpartum.

References

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/premature-ventricular-complexes-treatment-and-prognosis

- https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/epub/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042434

- https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Ventricular-Arrhythmias-and-the-Prevention-of-Sudden-Cardiac-Death

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)