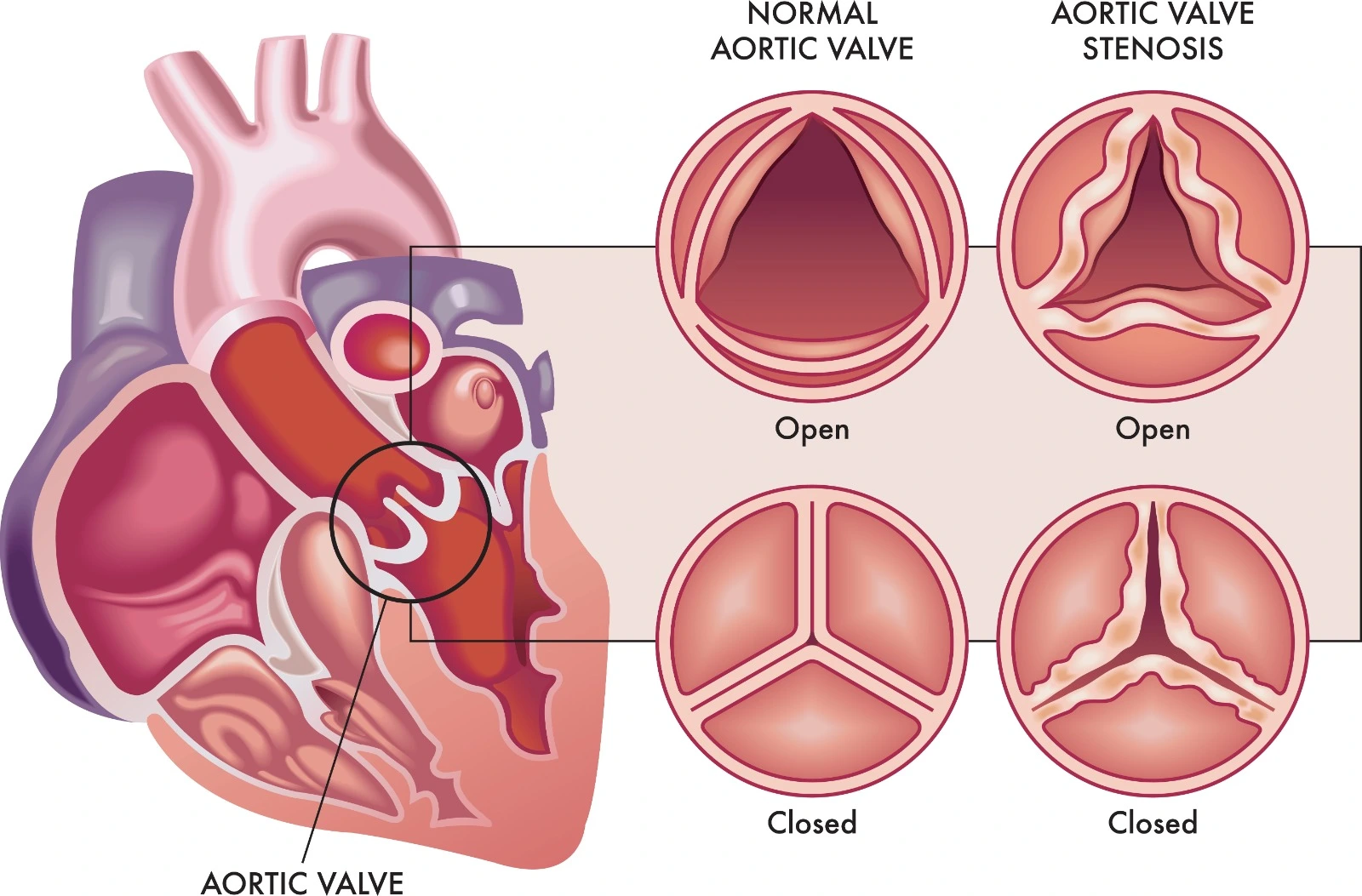

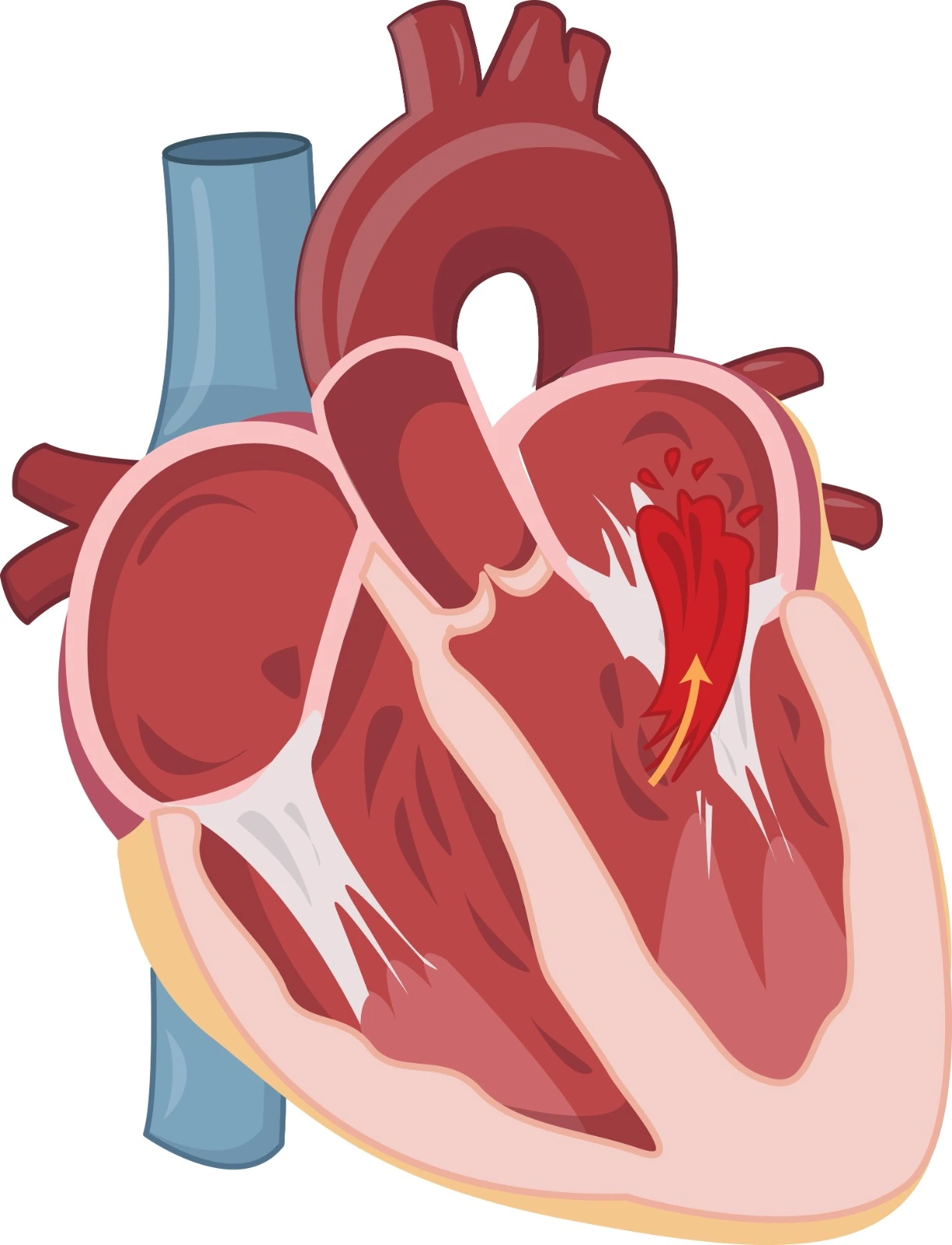

The aortic valve is also called the aortic semilunar valve based on its shape and is considered a tricuspid valve because it consists of three leaflets that move away to open the valve and allow oxygenated blood movement during systole from the left ventricle to the aorta, then close back during diastole to prevent any blood leakage to both sides.

Aortic stenosis is one of the most common and critical valvular heart diseases. It occurs when the aortic valve becomes narrowed and unable to be fully opened, which leads to the impediment of normal blood ejection from the left ventricle into the aorta and body circulation.

Pathophysiology

Aortic stenosis and a reduction in blood outflow result in an elevation of left ventricle systolic pressure. Then, as a compensatory mechanism, concentric left ventricular hypertrophy is developed, which affects left ventricle relaxation and compliance during diastole. However, it maintains systolic function, but it may not be adequate during physical activities.

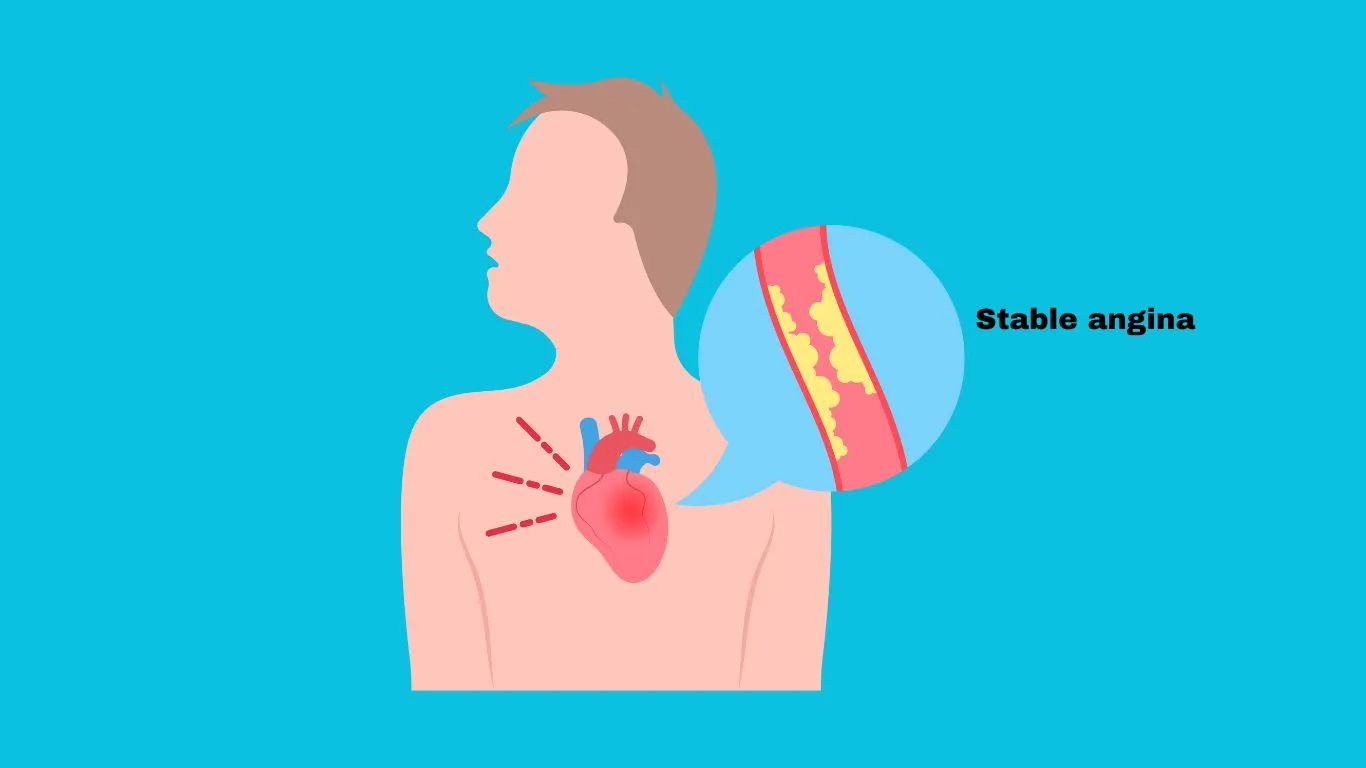

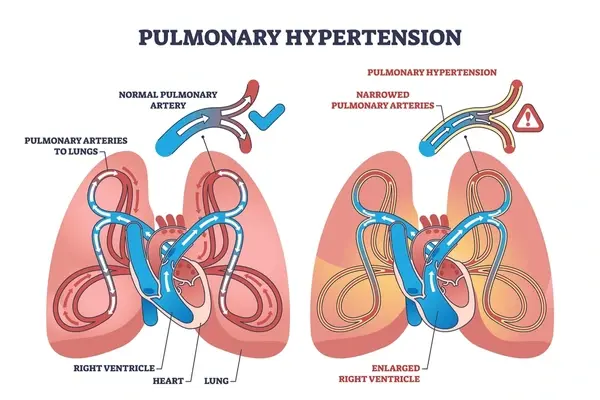

With time, left ventricle end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP) is elevated, which raises the pressure in the pulmonary circulation and afterload, so left ventricle diastolic dysfunction is worsened. At this stage, cardiac output and systolic function are no longer maintained, which leads to inadequate perfusion along with increased oxygen demand, which contributes to angina and myocardial ischemia. This condition is aggravated in the case of atrial fibrillation.

Etiology

- Congenital valvular aortic stenosis

Inborn valvular malformations related to tricuspid dissimilarity or cusps fusion resulted in turbulence formation and resulted in valvular injury, fibrosis, valvular calcification and rigidity, and valvular orifice narrowing or obstruction.

Unicuspid aortic valve, where the aortic valve only consists of one leaflet. It is common during childhood and associated with severe valvular obstruction, frequent symptoms, and high mortality.

The bicuspid aortic valve is not usually associated with severe valvular stenosis initially; rather, the valvular orifice narrowing worsens over years, so symptoms develop later in life; therefore, it is common in adults after the age of forty.

- Acquired valvular aortic stenosis

- Degenerative calcific aortic stenosis, also known as senile calcific aortic stenosis, is common in the elderly. Hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and smoking may induce endothelial damage and progressive calcification of the valve.

- Rheumatic heart disease causes fibrosis and calcification of the aortic valve cusps, valvular edge retraction, and commissural fusion.

- Paget disease is associated with increased cardiac output and heart failure, which increases the blood turbulence across the aortic valve and results in valvular injury, fibrosis, calcification, and stenosis.

Diagnosis

Although some patients may be asymptomatic, others may have complained of dyspnea, shortness of breath, syncope, and exertional angina.

It is essential as a clue for aortic stenosis persistence but can't be used for exclusion. A significant condition is associated with a single second heart sound since aortic closure is delayed, a noticed fourth heart sound, a slow-raising low-volume carotid pulse in patients without vascular changes, and a systolic murmur upon right intercostal space as it can be accompanied by aortic valve regurgitation.

- Transthoracic Echocardiogram (TTE)

It reveals aortic valve leaflet numbers, structure, thickening, systolic aortic valve leaflet rigidity, and left ventricle hypertrophy.

- Transesophageal Echocardiography (TEE)

It may be used to get clear aortic valve images.

It determines aortic stenosis severity through measurements of trans-aortic valve velocity (normally around 1 meter/second), the pressure gradient between the left ventricle and aorta, and the aortic valve area.

Staging and Severity of Aortic Stenosis

- Stage A: At Risk of Aortic Stenosis

When an aortic valve structure abnormality is detected, the reduced maximum aortic valve velocity is below 2 m/s without any symptoms.

- Stage B: Progressive Aortic Stenosis

Aortic structural abnormality is identified, along with left ventricular diastolic dysfunction but preserved ejection fraction, without any symptoms.

- Mild Aortic Stenosis: maximum aortic valve velocity is 2-2.9 m/s or mean pressure gradient is <20 mmHg.

- Moderate aortic stenosis: maximum aortic valve velocity is 3–3.9 m/s or mean pressure gradient is 20–39 mmHg.

- Stage C: Asymptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

Abnormal aortic structure with severe calcification and stenosis, but without symptoms.

- Stage C1: left ventricle hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction, with normal ejection fraction.

- Stage C2: Left ventricle ejection fraction <50%.

Severe aortic stenosis: maximum aortic valve velocity is ≥4 m/s or mean pressure gradient is ≥40 mmHg. Also, the aortic valve area is ≤1 cm2.

Very severe Aortic stenosis: maximum aortic valve velocity is ≥5 m/s or mean pressure gradient is ≥60 mmHg.

- Stage D: Symptomatic Severe Aortic Stenosis

References

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)