Overview

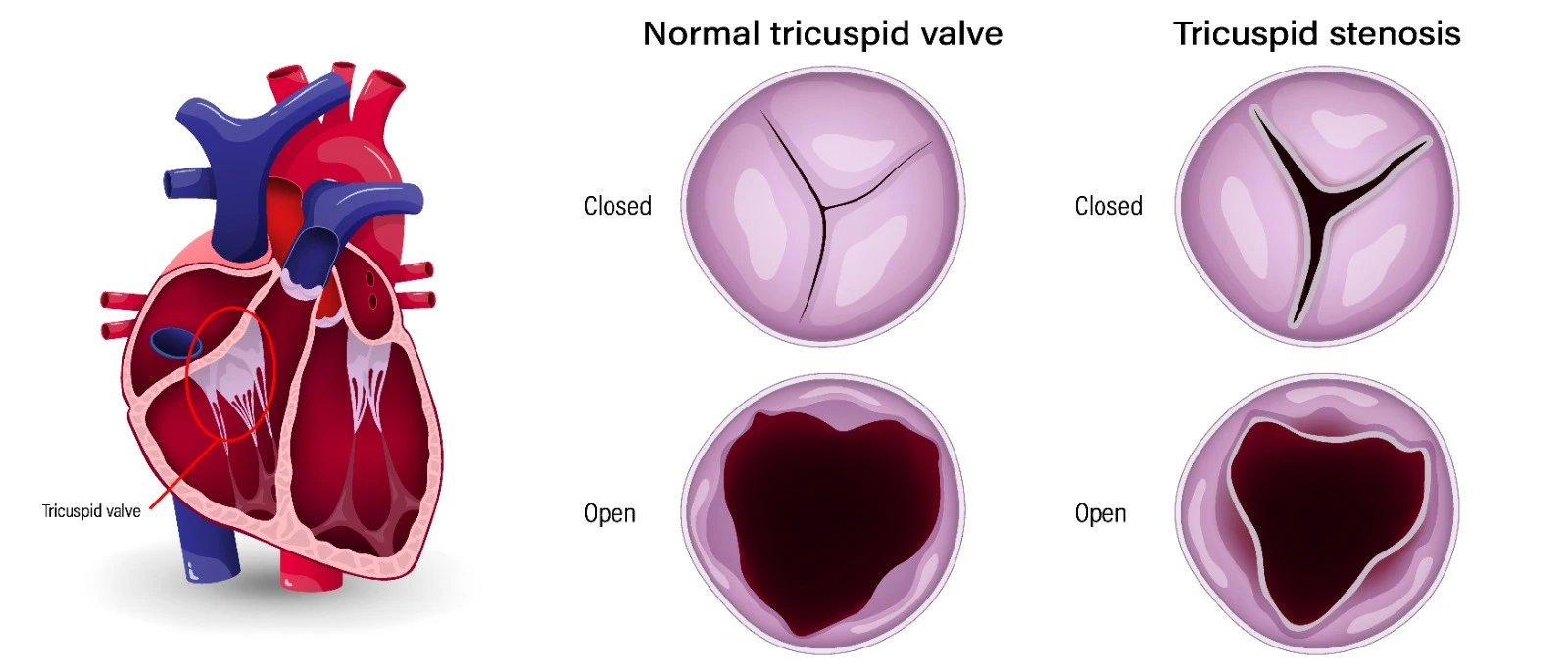

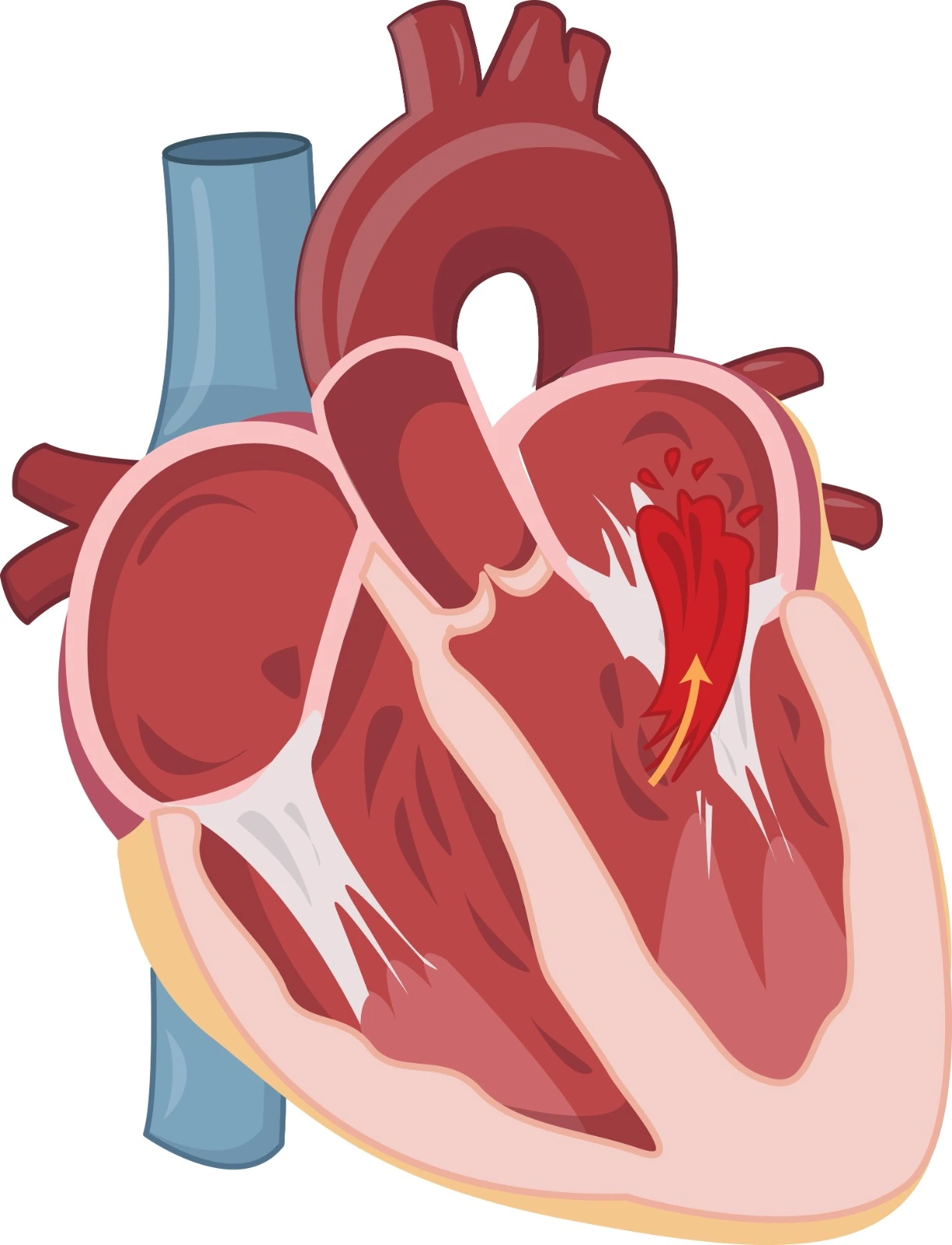

Tricuspid valve diseases happen when the normal function of the tricuspid valve isn't achieved. In a normal state, the tricuspid valve opens and closes to ensure that blood flows in one direction from the right atrium to the right ventricle to the lungs. Sometimes this valve cannot open and close properly, resulting in blood backflow from the right ventricle to the right atrium: Tricuspid valve regurgitation (TR), other times the valve might become narrowed, not allowing the blood to flow from the right atrium to the left ventricle: Tricuspid valve stenosis (TS)

Etiology

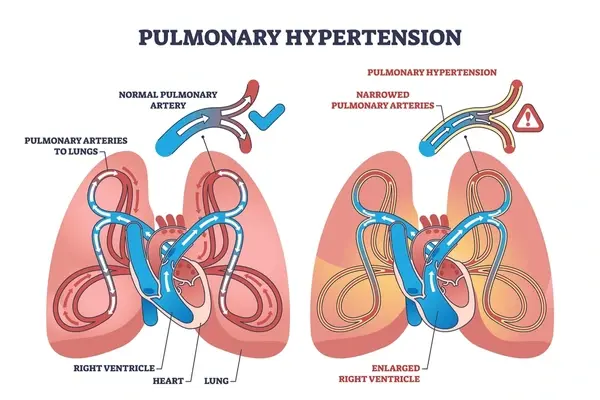

Tricuspid valve regurgitation might be primary or secondary. Primary TR is less common and has many causes: Endovascular pacemaker defibrillator, chest wall or deceleration injury trauma, infective endocarditis, Ebstein anomaly, rheumatic valve disease, carcinoid syndrome, ischemic heart disease affecting the right valve with rupture or papillary muscle dysfunction, myxomatous degeneration associated with tricuspid valve prolapse, connective tissue disorders, Marantic endocarditis with SLE and RA, Drug-induced (Fenfluramine, Phentermine, Pergolide), whereas secondary TR is more common and defined as regurgitation with no anatomical defects, it happens due to any condition that elevates the right ventricular pressure or pulmonary hypertension that leads to dilation in the right atrium, right ventricle, and tricuspid annulus.

Tricuspid valve stenosis is commonly of rheumatic origin, and it often occurs with tricuspid valve regurgitation.

Pathophysiology

- Tricuspid valve regurgitation:

TR happens when blood backflows from the right ventricle to the right atrium due to its inability to open and close adequately. In mild-moderate cases, this does not lead to any hemodynamic consequences, but in severe cases where this backflow results in an increase in right atrial and venous pressure, patients will develop heart failure signs and symptoms.

- Tricuspid valve stenosis:

The narrowing or stiffness of the tricuspid valve results in a persistent diastolic pressure gradient between the right atrium and ventricle that increases with exercise and inspiration and, in significant cases, might lead to venous congestion features: jugular venous distention, ascites, and peripheral edema.

Clinical Manifestations

- Tricuspid valve regurgitation

Symptoms: usually no symptoms in mild-moderate cases, but in severe cases, there might be a pulsatile sensation in the neck and right-heart failure symptoms: eg: ascites. (2) Sometimes symptoms arise from the underlying cause.

Physical examination: with severe right-sided heart failure, patients appear: cachectic, chronically ill, cyanotic, and sometimes jaundiced.

Jugular vein:

- Distinct "c-v" wave

- Pulsatile that might be confused with carotid pulse

- Kussmaul's sign

Palpation:

- Dynamic Right ventricular heave

- Dilated pulmonary artery in cases of pulmonary hypertension

- Pulsation along the right sternal border in severe cases

Edema

- Ascites and peripheral edema

- Anasarca in severe cases

- Unilateral or bilateral pleural effusion in pulmonary hypertensive patients

Hepatomegaly

- Enlarged and tender liver

- Pulsatile liver in severe cases

- In some cases, a systolic murmur can be heard over the liver "with a thrill".

Cardiac Auscultation

- Murmur: holosystolic murmur that can be heard at the right or left mid-sternal border or the subxiphoid area. However, it is often absent, even in severe cases.

- Murmur will be augmented with certain interventions: leg raising, exercise, and hepatic compression.

- Standing might diminish the murmur's intensity.

- In patients with pulmonary hypertension: the murmur's intensity changes with a change in pulmonary artery pressure.

- S3 might be heard with an extremely dilated right ventricle.

- S4 might be heard with right ventricular hypertrophy.

- In patients with pulmonary hypertension: splitting of S2 and increased P2 intensity

- Mild TR: no ECG changes except for nonspecific ST and T wave abnormalities in the right precordial leads.

- Patients with right ventricular infarction: Q waves in leads V3R and V5R in right-sided precordial leads

- Patients with pulmonary hypertension: RV hypertrophy with right axis deviation and tall R waves in V1 and V2 and rarely right bundle branch block. (2)

- Chest radiograph: cardiomegaly, prominent cardiac silhouette, and reduced retrosternal space

Symptoms

- Abdominal discomfort due to hepatomegaly

- Fatigue and effort intolerance

- Fluttering discomfort in the neck

Physical examination

- Jugular venous distention and pulsation, hepatomegaly, hepatic pulsation, ascites, peripheral edema, and anasarca sometimes

- Patients with co-existing mitral valve disease: signs of pulmonary congestion

- A diastolic murmur in the lower left sternal border in the fourth intercostal space increases with maneuver, especially aspiration (Carvallo sign).

Labs:

Mild elevation in serum bilirubin; ALT and AST are normal or mildly increased; albumin is normal or mildly depressed.

Chest radiograph:

It is not necessary unless the patient has dyspnea.

ECG:

This is not indicated unless the patient has other valvular heart disease (AFIB).

Treatment:

- Managing the underlying cause

- Diuretics for patients with fluid overload, especially due to heart failure. An aldosterone antagonist may provide additional benefits for patients with Heart failure and TR.

- Surgery is recommended for patients with severe TS, even if they are asymptomatic.

- Surgery is recommended in patients with severe TS undergoing left-sided valve intervention.

References

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5494422/

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/etiology-clinical-features-and-evaluation-of-tricuspid-regurgitation

- https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Valvular-Heart-Disease-Guidelines

-

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/management-and-prognosis-of-tricuspid-regurgitation

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)