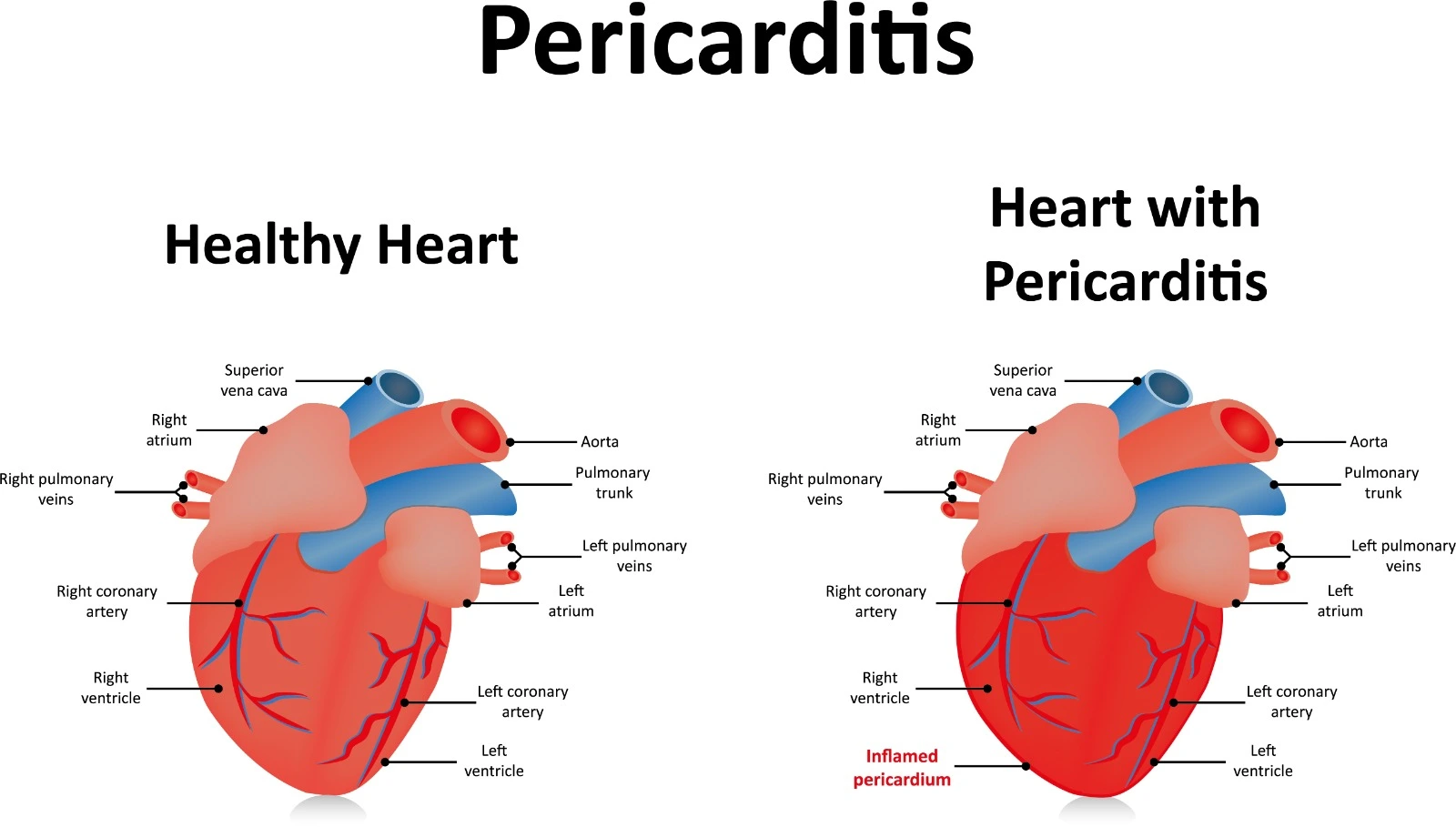

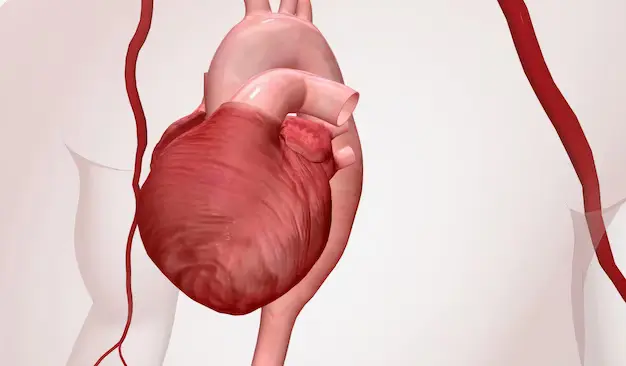

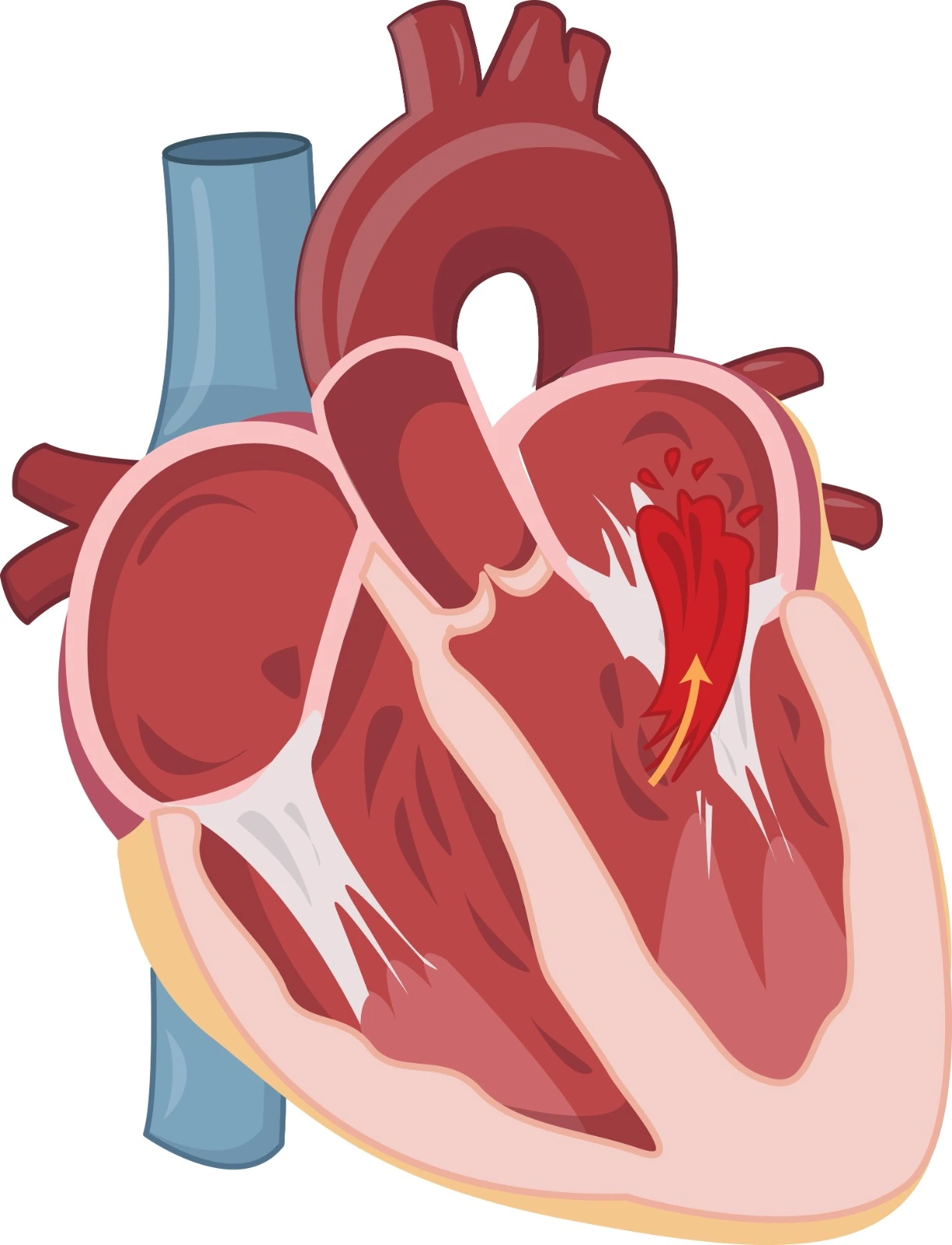

The pericardium is the membranous sac that encloses the heart, serving to protect and support this vital organ. It is composed of two main layers: the outer fibrous pericardium, which provides structural integrity and protection, and the inner serous pericardium. The serous pericardium, in turn, consists of two layers connected at the root of the great vessels: the outer parietal layer, which lines the fibrous pericardium, and the inner visceral layer, which covers the entire surface of the heart. Between these serous layers, a small amount of serous fluid is present, which acts as a lubricant, allowing the heart to move smoothly within the pericardial sac and reducing friction.

Chronic inflammation of the pericardium, a condition known as pericarditis, can lead to structural changes in the pericardium, potentially affecting ventricular relaxation during the heart's diastolic phase. This inflammation can impact the heart's function and overall health.

Pathophysiology and etiology

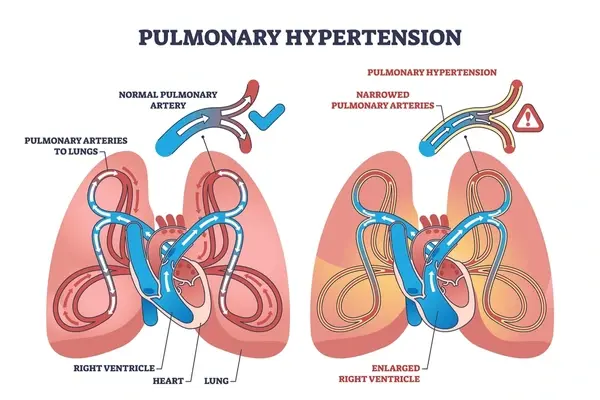

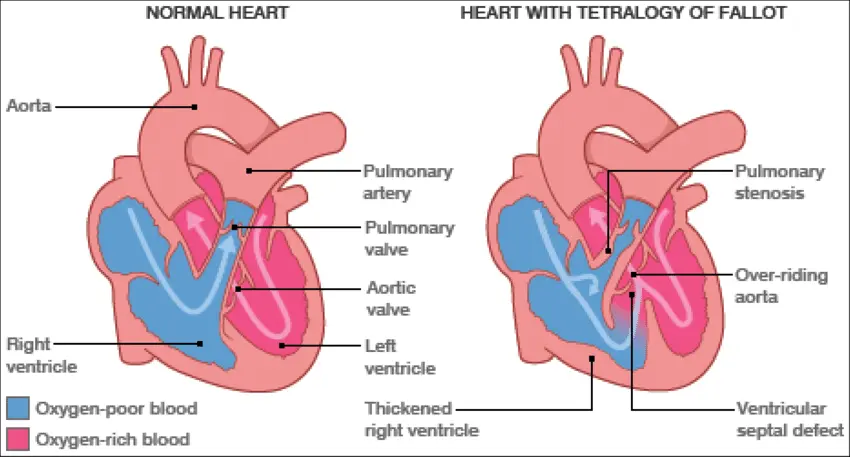

If the inflammation has occurred in the pericardium layers, it will lead to calcification, fibrosis, and scarring that results in the thickening and fusion of the pericardium layers and loss of the inflation ability of the heart during the filling of ventricles. Consequently, venous return will be limited as ventricular pressure is increased while preload and ventricular filling are decreased after early normal ventricular filling that is maintained through the normal myocardium of ventricles.

If pericardium infection spreads to the myocardium and leads to structural changes, the systolic function of the ventricles will be affected, so the cardiac output will be reduced progressively.

Constrictive pericarditis major causes include:

- The majority of constrictive pericarditis cases are found to be idiopathic, with the thought that they may be related to a previous undiagnosed viral pericarditis.

- Acute bacterial pericarditis may develop into constrictive pericarditis within 6 months.

- Therapeutic radiation may cause constrictive pericarditis in the long term through endothelial damage and subsequent inflammatory processes.

- Cardiac surgeries where an incision is made in the pericardium layers may lead to inflammation and constrictive pericarditis.

- Minor causes may include fungal infections, uremia, and neoplasms that are involved in pericardial effusion; chronic pericardial effusion associated with autoimmune disorders; post-myocardial infarction; chest wall trauma; and some medications.

Clinical Presentation

Constrictive pericarditis may be associated with various clinical symptoms that usually develop over years and are related to the pathogenesis and complications of constrictive pericarditis. These symptoms may include:

- Fever, diaphoresis, tachycardia, and chest pain are related to acute infection.

- Dyspnea, orthopnea, and peripheral and pulmonary edema are associated with congestive heart failure.

- Abdominal congestion, nausea, vomiting, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain are associated with hepatic congestion.

Diagnostic Considerations

I) A physical examination may reveal several findings that may involve the following:

- Sinus tachycardia and muffled heart sounds may be noticed. A heart murmur is usually associated with coexisting valvular diseases.

- Pericardial knock: an audible, non-palatable heart sound detected earlier than the third heart sound.

- Pulsus paradoxus, where systolic blood pressure is decreased by more than 10 mmHg during inspiration due to cardiac output reduction, may be noticed with pericardial effusion in addition to constrictive pericarditis.

- Kussmaul sign: as jugular vein pressure is elevated during inspiration rather than falling, it is related to right ventricular dysfunction.

- Steep Y descent in atrial waveform during early diastole as the ventricular filling is maintained

- Dip-and-plateau sign or square root sign in the ventricular waveform, where the ventricular filling is reduced and ventricular pressure is increased after the early diastole phase due to stiffed ventricles.

- Hepatomegaly and ascites may be noticed.

II) Laboratory tests may show disease complications or an underlying cause.

- Elevated C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rates are associated with inflammation.

- Leukocytosis, as WBCs are elevated in cases of infection.

- Elevated liver enzymes, bilirubin, and hypoalbuminemia are associated with hepatomegaly and congestion.

- Elevated cardiac biomarkers, such as brain natriuretic peptide, along with metabolic acidosis, may be associated with heart failure.

III) Chest radiography usually has low specificity and sensitivity but may be able to detect severe pericardial calcification.

IV) Echocardiography findings are not usually remarkable but may detect any thickness in the pericardium, vein distention, and ventricular dysfunction.

V) Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can prclearly visualizehe the pericardium.

References

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)