Overview

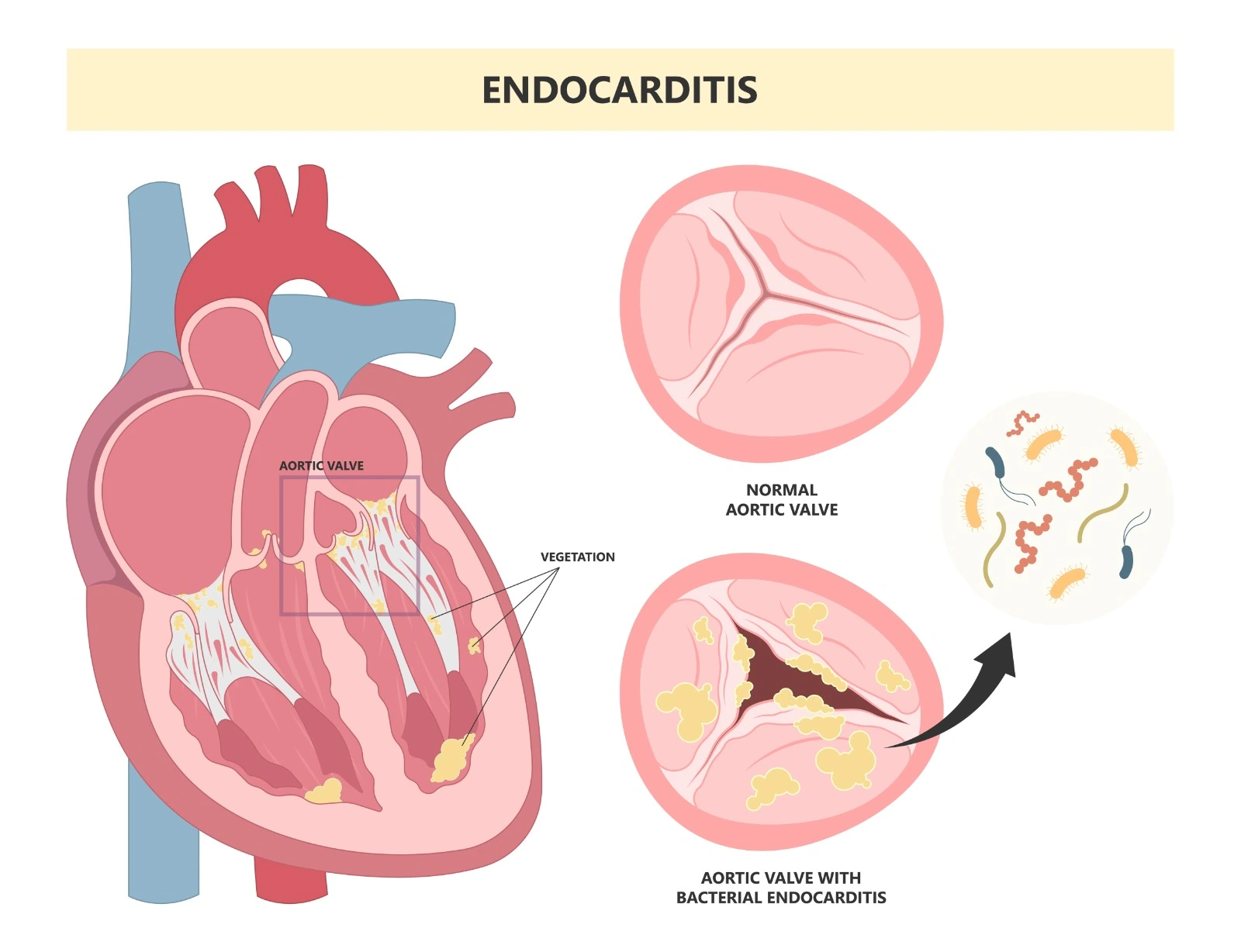

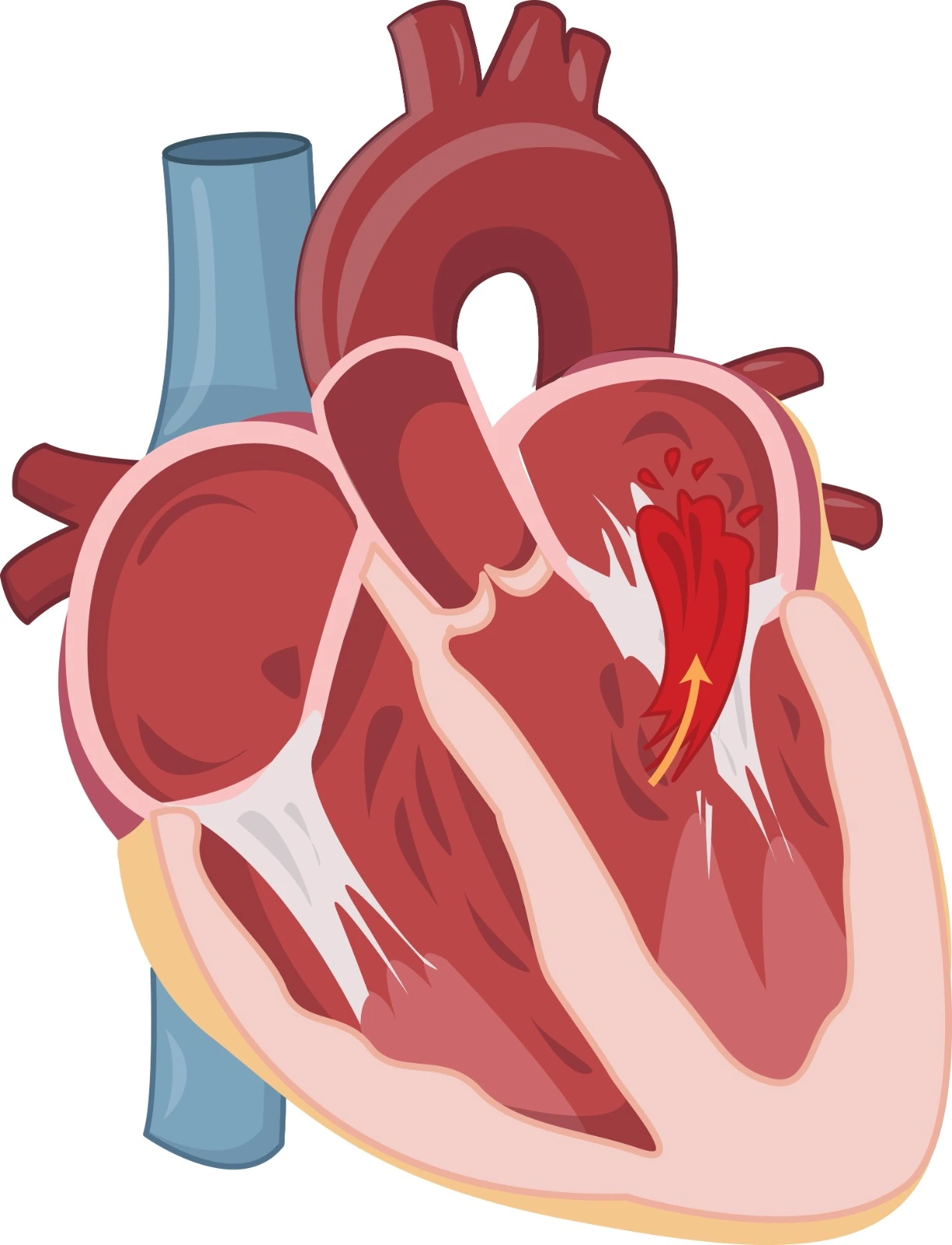

The infection of the endocardium, the heart's inner lining, and the valves that divide its four chambers is known as infectious endocarditis. It occurs through different microorganisms that typically affect native heart valves. This infection is usually secondary to a primary infection of the bloodstream (bacteremia). Sometimes it might affect non-vulvar areas and implanted materials.

Although fungi and other microorganisms might lead to infectious endocarditis, bacteria are considered the most commonly occurring pathogen.

Epidemiology and Etiology

- Native valve endocarditis can be community-acquired or hospital-acquired.

- Hospital-acquired: if >= 48 hours of exposure to a healthcare setting.

- Community-acquired: within 48 hours of hospital admission. The incidence of this condition is variable due to the differences in predisposing factors between different areas.

- Prosthetic valve Endocarditis: happens in patients who undergo valve replacement; it occurs in 1-6% of patients with heart prostheses and in 20% of people with endocarditis. The infection might be early within 2 months after surgery or delayed after 12 months of surgery. Infections occurring 2-12 months apart are mixed between delayed nosocomial and community-acquired infections.

Pathophysiology:

- Native valve endocarditis:

It is a result of bloodstream infections that allow bacteria to reach the heart valves. As the pathogens do not adhere to normal endothelium, endothelium damage or injury is essential for microorganisms to adhere and colonize.

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis:

The pathophysiology of early prosthetic valve endocarditis begins intraoperatively and invades the implanted valve, or it can spread through the blood within days to weeks. This allows the microorganisms to have direct contact with the prosthesis-annual interface and the fibrinogen and fibronectin in the paravalvular area through the sutures, leading to abscesses in both mechanical and bioprosthetic valves, whereas late prosthetic valve endocarditis happens months after the procedure, in which micro-thrombus forms due to endothelialization in the vulvar and paravalvular areas. The bacteria adhere to this micro-thrombus and lead to endocarditis.

Microbiology

- Native Valve Endocarditis:

- The most common microorganisms are Staphylococci, Streptococci, and Enterococci.

- Gram-negative bacteria are less commonly seen, eg: E. coli.

- Brucella is common in areas where it is endemic.

- Fungal: rare, but Candida Spp. and Aspergillus Spp. are the most commonly seen pathogens.

- Prosthetic valve endocarditis:

- Within 2 months of implantation, the most commonly seen pathogens are S. aureus and coagulase-negative staphylococci, followed in frequency by gram-negative bacilli and Candida Spp.

- Between 2 and 12 months of implantation: coagulase-negative staphylococci, S. aureus, and streptococci, followed by enterococci.

- Beyond 12 months of implantation: streptococci, S. aureus, followed by coagulase-negative staphylococci, and enterococci.

Diagnosis

Infective endocarditis should be considered in all patients with sepsis or unexplained fever in the presence of risk factors. The initial clinical assessment should take into consideration cardiac and noncardiac risk factors, physical examination, and supportive clinical context.

- Previous infective endocarditis

- Valvular heart disease

- Prosthetic heart valve

- Central venous or arterial catheter

- Transvenous cardiac implantable electronic device

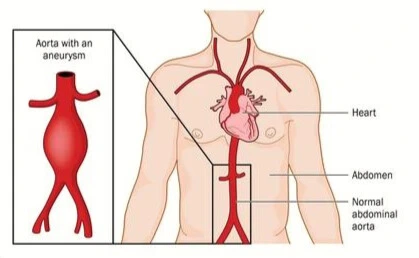

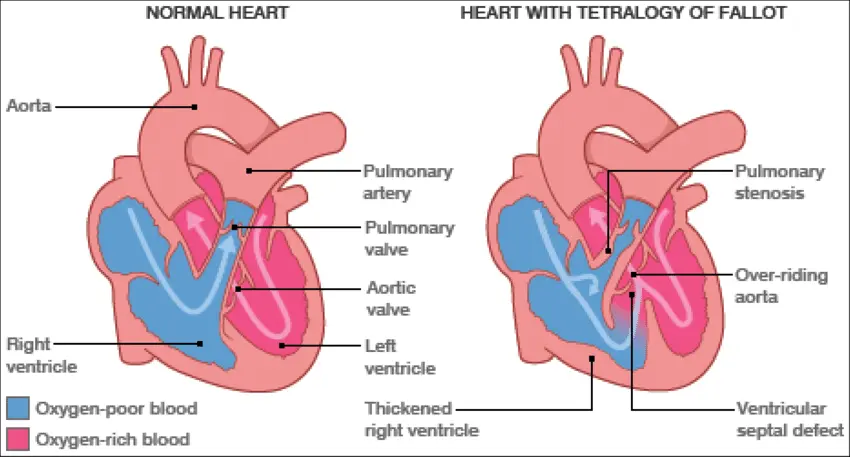

- Congenital heart disease

- Central venous catheter

- People who inject drugs

- Immunosuppression

- Recent dental or surgical procedures

- Recent hospitalization

- Haemodialysis

Management:

- No empiric therapy is necessary for patients with no acute symptoms and can be delayed until blood culture results are available.

- Patients with acute symptoms: obtaining at least two and preferably three sets of blood cultures from different venipunctures, spaced over 30-60 minutes, followed by empiric antimicrobial therapy taking into consideration the most likely pathogen.

- Community-acquired NVE or late PVE (≥ 12 months post-surgery): ampicillin with ceftriaxone or flucloxacillin and gentamicin.

- Early PVE, or nosocomial and non-nosocomial healthcare-associated IE: Vancomycin or Daptomycin combined with Gentamicin and Rifampin

- Community-acquired NVE or late PVE (≥12 months post-surgery) who are allergic to Penicillin: cefazolin, or vancomycin in combination with Gentamicin

- Endocarditis due to oral Streptococci and Streptococcus gallolyticus group: Penicillin G, Amoxicillin, and Ceftriaxone are the first-line choices.

Duration: 4 weeks in native valve endocarditis, 6 weeks in prosthetic valve endocarditis. Vancomycin is an alternative in cases of penicillin allergies.

- NVE due to Staphylococcus infection: flucloxacillin or cefazolin for 4-6 weeks.

- PVE due to Staphylococcus infection: flucloxacillin or cefazolin with Rifampicin for 4-6 weeks and Gentamicin for 2 weeks.

- NVE MRSA: Vancomycin for 4-6 weeks.

- PVE MRSA: Vancomycin with Rifampicin for 6 weeks and Gentamicin for 2 weeks.

- NVE or PVE Enterococcus: Ampicillin or Amoxicillin with ceftriaxone for 6 weeks or with Gentamicin for 2 weeks.

References:

- Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiological Approach, 12th edition

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/native-valve-endocarditis-epidemiology-risk-factors-and-microbiology

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/prosthetic-valve-endocarditis-epidemiology-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567731/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544293/

- https://www.escardio.org/Guidelines/Clinical-Practice-Guidelines/Endocarditis-Guidelines

- https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-management-of-infective-endocarditis-in-adults

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)